Ketchum’s early boomtown days are a colorful period of growth and progress. Yet amidst these early stories, the history of the town’s namesake, trapper and mountain man David Ketchum, still remains a bit muddled. A letter from 1927 sent to E. N. Ebbe of Ketchum’s Kamp Hotel from James L. Richardson—whose time in the area overlapped with David’s—referenced his legacy.

“[David] was spoken of as one of the outstanding characters of the country on account of his personality,” James wrote. “ … My impression of him is that of being a tall, slim, wiry man, with long whiskers, as was the style among most of the men there, of a kindle genial disposition, but withal one not to take liberties with.”

Nearly a century later, a plaque at the Overlook on Bald Mountain with a quote from David dated “circa 1890” reveals a look into the Ketchum he once knew.

“They want’d t’ call th’ town Leadville, but th’ govrn’mnt said there was too many already. So they settled for Ketchum and I’m right proud they did. After all, I built th’ first cabin here back in ’79 … Course th’ way th’ silver’s runnin’ out, might not matter what th’ town’s name is anyhow. …”

This dim outlook on his namesake home might take you by surprise. But at the end of the 19th century, the Wood River Valley was transitioning from a time of vibrant development and exciting growth to the threat of becoming yet another ghost town.

According to the Idaho Historical Society, 1879 marked the end of the Bannock Indian War that forced American Indians to relocate and leave the Wood River Valley. The conclusion of the conflict opened up the opportunity for hopeful early settlers to explore the surrounding terrain. Miners and mountain men hurried to the site by the thousands to stake claim, driven by promises of prospecting silver and lead.

After locating a silver lode near the junction of the Big Wood River at Warm Springs Creek and some lead ore elsewhere, reportedly near Galena, David built a modest cabin near a hot springs to store supplies for the winter of 1879. According to some, the site was the Guyer Hot Springs about three miles west of Ketchum along Warm Springs Creek. There, he settled in for a snowbound winter.

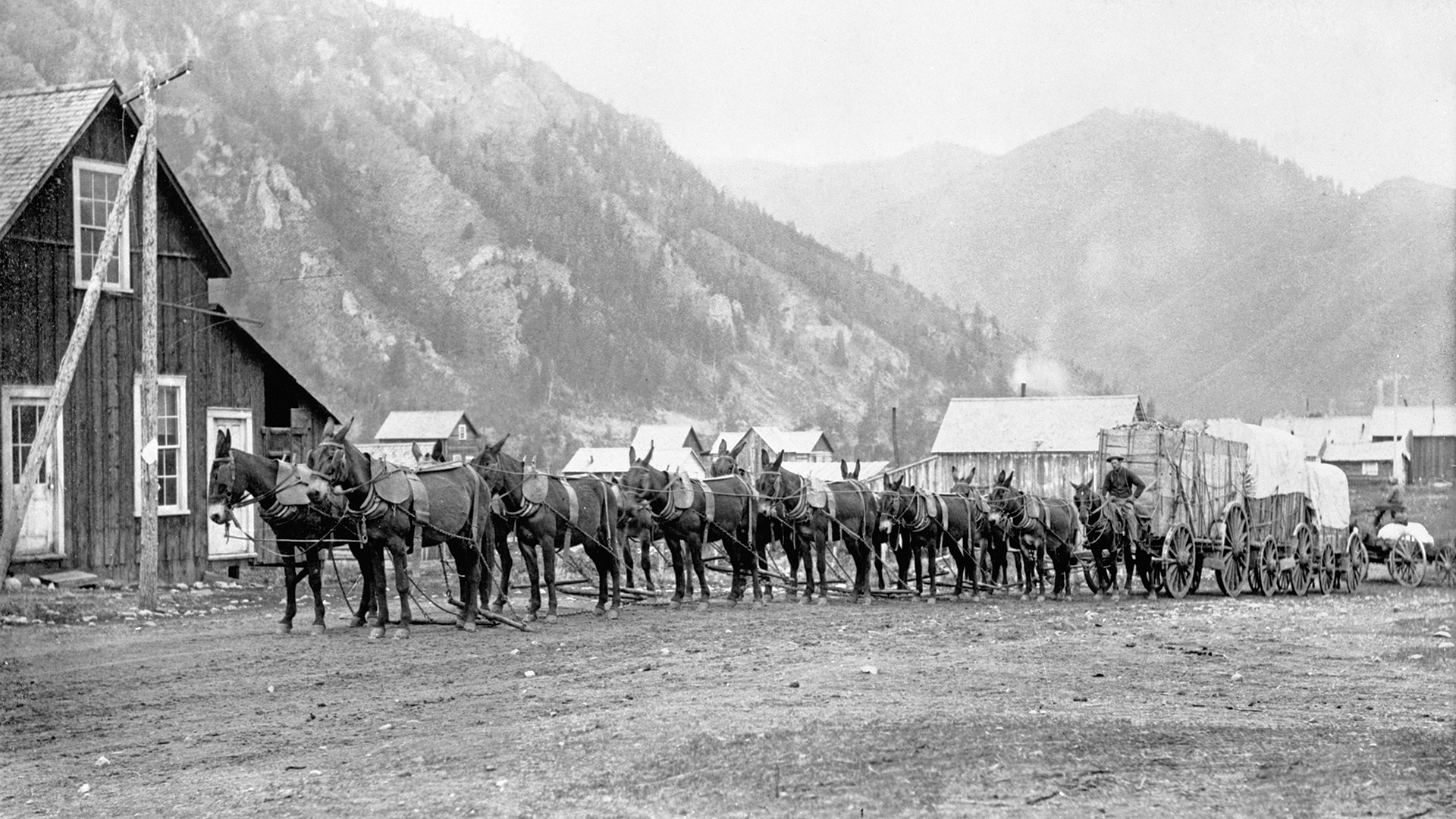

David’s arrival marked the beginning of the Wood River Valley as a boomtown, led by prosperous mines unearthing valuable silver. During those early years, the region had two banks, two hotels, six livery stables, a newspaper, and ample saloons, according to the Idaho Historical Society. The Union Pacific Railroad also came to town, making Ketchum its northern terminal, and early tourism was an anchoring part of the community during this period as well.

But the young town needed an official name.

The story goes that the first settlers were already calling the region Leadville, but nothing was official just yet. They submitted an application for a post office bearing the new name, but it was promptly rejected. Leadville, Colorado, had already been founded a few years prior. An application was resubmitted, according to the Association of Idaho Cities, but this time with the name Ketchum, honoring the town’s first settler. It became official, and Ketchum was born.

Some paper clippings from the 1870s and 1880s provide a glimpse into the life of David Ketchum during his time in the Wood River Valley and beyond.

The boom continued on, and life in Ketchum was thriving for the next decade. Once silver began to decline in value, however, the growth halted. The smelter closed, and the outlook was looking grim.

As noted in the second half of his quote, David could see the writing on the wall: “Folks is already headin’ for th’ new boomtowns. Heck, we got more dogs than people now’days… Wonder what’ll happen t’ ol’ Ketchum. Prob’ly dry up an’ blow away…”

But thankfully, David’s predictions were wrong. Two other predominant industries, tourism and agriculture, kept the town afloat. But it seems David didn’t stick around long enough to see it continue.

Ketchum native Mary Jane Griffith Conger, author of “The Chronicles of Ed Price,” told the Idaho Mountain Express that David up and left town during the mining decline, contrary to town rumors. “We heard he had been killed in a bar brawl, but it turned out he went back to Missouri and made a fortune selling Indian medicines,” she said in the 2011 article.

Originally from Missouri, David had made his way west around 1870. A census taken in July 1870 from Bozeman, Montana, contained a David Ketchum, 29 years old, from Missouri, who was listed as a woodcutter. While the great Silver Rush lured him south to Idaho nine years later, David had also been known to travel farther west. An article from the Idaho Semi-Weekly World, dated January 7, 1881, stated David was in the butcher business with Brown & Hull in San Francisco. According to the article, Ketchum, “now one of the bonanza kings of the Wood River, is spending the winter at The Bay.”

Wherever life eventually led him, David’s mark on the Wood River Valley was made. In his letter, James L. Richardson called David a pioneer “whose contribution towards the development of the country will, in history, go down unsung.”

Many questions about David remain, but one thing is for certain: his legacy is deeply seated in Ketchum’s history.