Before the train, central Idaho was the terrain of a free-running freestone river; it was where the Shoshone-Bannock tribes came to fish; it was where prospectors and trappers came seeking fortunes. It was what the writer Mary Hallock Foote called “the darkest part of darkest Idaho” in 1882 when her engineer husband got involved with the Wolftone Mine.

Then the train arrived—its throbbing energy surely reverberating through the mountains, the whistle perking the ears of wolves, and its steel circulation system changing the flow of the valley.

In the 1880s, the Oregon Short Line tracks were punched north from Shoshone, reaching Ketchum by 1884 and linking the wilds of central Idaho with a global industrial economy. Millions of dollars of galena ore rolled down those tracks in the 1890s, and around that time tourists in top hats and dresses swept into town on those same tracks, then traveled by horse-drawn wagon to Guyer Hot Springs Resort in Warm Springs Canyon to rejuvenate in high elevation hot water.

In the first half of the twentieth century, hundreds of thousands of sheep were shipped down those rails. Later, at the behest of Union Pacific Railroad chairman and Sun Valley Resort founder, W. Averell Harriman, skiers started arriving on special event trains, such as the Snowball Express party train that brought revelers from Los Angeles as late as the 1960s. They’d be met with a “western welcome” and ferried to Sun Valley Resort in horse-drawn surreys and wagons.

Much of this circulation happened at the loop—the northernmost point of this spur of the Union Pacific railway system, where the tracks formed a broad circle in what is now the industrial district of Ketchum.

The loop lay just past the railway intersection where one track turned toward the Philadelphia Smelter at the mouth of Warm Springs; the loop was beyond the small Ketchum depot and the labyrinthine stockyard and weigh house. At the end of the line, the tracks circled wide around a sagebrush flat, glancing close to the Big Wood River near where the Presbyterian Church of the Big Wood now stands.

1883, Oregon Short Line (OSL) completed to Hailey Depot and, in 1884, to Ketchum, Idaho.

Many days, the loop lay quiet. Supply trains came and went with no fanfare or commotion, especially as the twentieth century advanced. Even as they kept the lifeblood of the community going, bringing coal for the resort and even shipping linens from the hospital to Utah to be laundered, those iron-and-steel engines didn’t intersect with most Sun Valley routines.

Each July and August, though, in the 1940s and ‘50s, the loop was electric with activity as bands of sheep were trailed from the high country and loaded onto waiting trains. The sheep were staged overnight on the bench where Zenergy and the Big Wood Golf Course are now, then pushed to the stockyard to be weighed and shipped to distant markets. The loop roiled with dust and smoke, the squeals of locomotive brakes and the bleating of sheep, the smell of wool and dung and smoke, and the yells of men.

1972, Ketchum Depot closed. Hailey, Belleview, and Picabo had already closed.

“I was rousted from bed at 4 a.m.,” recalls Jack Lane, Sun Valley resident, who, as the son of a prominent local merchant, was enlisted to help with the shipping. The sheep were weighed and herded through the stockyard’s maze of wooden fences, gates, and chutes to be loaded.

At the top of a chute, a little boy—like Jack—led the first bell-clad ewe into and around the boxcar. Jack remembers hunkering near the boxcar door while the sheep crowded the car and Basque sheepherders pushed poles through the slats to nudge the sheep along.

The payoff at the end of a hot day shipping sheep for a little boy like Jack “was to ride up with the engineer around the balloon track in the steam engine,” says Jack. They rounded the loop in the dusty afternoon heat, and seven-year-old Jack pulled on the whistle and felt a rush of exhilaration. From aboard the locomotive, the world loomed large.

1987, Union Pacific Railroad pulled up the tracks and ties.

Ketchum resident Peter Gray also remembers the summer sheep-shipping ritual at the railroad loop—and he grins recalling the early morning pancakes-and-bacon breakfast with the sheepmen at the Western Café when he was a young boy.

“It was the guys, you were with your fathers,” recalls Peter. Those mornings of hard work between the stockyard and b

An aerial view pf the railroad depot loop at the end of the line in Ketchum, August 1957

oxcars inducted these Idaho boys into a world of western men and labor. They relished it.

At that time, in the 1950s, sheep-shipping season was the busiest time at the railroad loop. Otherwise, “the train up there was not part of the social fabric of the community,” Peter says. It brought supplies and sometimes tourists (the main passenger service ended at Shoshone), but it was at the periphery of daily experience. Its whistle was heard in the distance, but it didn’t intersect with one’s lived routine.

By the early 1970s, few trains traveled to Ketchum, and a final special event train, the Preamble Express, pulled into Ketchum in 1976. By 1987, the tracks were gone.

Ketchum resident Gail Severn was a little girl when the trains still ran in the Wood River Valley, and her grandfather was a lead conductor for Union Pacific Railroad. She lived in Nampa as a child, and sometimes her grandfather would pick her up for the trip from Boise to Ketchum. Her eyes spark with memories of riding the train—“It felt special; it was a big deal!”—and she remembers the flash of the sagebrush landscape beyond the train windows, and the warm hand of a black porter leading her down the aisle.

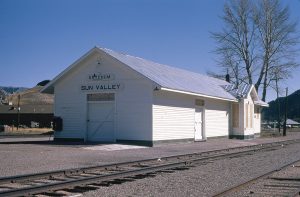

The Ketchum/Sun Valley rail depot during the days of passenger service and the Snowball Express direct from Los Angeles, circa 1940-1950

Today, traces of the train are hard to find where the railroad loop once dominated. The rail line was transformed into the valley-long bike path, and the Ketchum depot, stockyard, and turnaround have been replaced by construction company garages, the Big Wood Bakery Café, and the YMCA recreational facility. An interpretive sign harkens this history, like a secret, tucked behind the Mountain Rides bus stop at the entrance to the YMCA.

But just a few blocks from where the railway stockyard stood, you can still catch a glimpse of it in an unexpected place: At Gail Severn’s gallery, beyond the smooth, sleek blue of a stainless steel sculpture, and behind a bold-stroked oil painting on canvas, a series of plain brown posts quietly uphold the front desk. Gail salvaged this wood from the stockyard when it was dismantled in the 1980s, wanting to honor her grandfather and recalling the thrill she felt as a little girl riding past those stockyards in the caboose, running up and down the aisles of the train as it chugged along.

Where the railway reached the end of the Wood River Valley line, the pulse has changed: Now, cars and cyclists, tech workers and gallery walkers set the rhythm. But at the heart of that pulse a whistle still calls and tugs at the edges of memory.