It’s before dawn on January 1, 2009. The moon glows, just enough to illuminate the faint outline of the frozen Magic Reservoir. There’s no sound but the wind, the only lights those cast by lamps at cottages and mobile homes surrounding the lake. There’s not a soul on the ice but Paul Hopfenbeck and Bill Tormey. This is their annual pilgrimage to Magic to watch the sunrise on New Year’s Day.

Tormey and Hopfenbeck forego their usual supplies and take only necessities: poles, bait, headlamps, beach chairs, gas-powered auger, thermos of coffee and bottle of Bailey’s Irish Cream. Rather than transport the gear across the ice on a snowmobile or all-terrain vehicle, they opt to drag two plastic sleds, and they wait until they’re settled to use the headlamps, navigating by dawn’s reflection on the ice to guide them.

“To use a light would almost ruin it,” Hopfenbeck says.

Every year, these two Bellevue, Idaho, residents skip the parties and champagne, go to bed by nine and travel the 20 snow-swept miles to Magic before six in the morning. They’re often the only people out there, in part because it’s so early, in part because it’s so cold. Last New Year’s, the temperature registered 30 below zero.

“I can’t think of a better way to start the new year off,” says Tormey. “Nobody’s there. It’s just pure silence. And the serenity of your surroundings, man, you feel like you’re the only person on the earth.”

Their figures, alone in the dark on the moonlit ice, conjure a stereotype of weathered old ice fishers, lonely and scruffy men who squat by dark holes limply holding fishing poles in one hand and cans of beer in the other. By mere association, the words ice and fishing sound solitary and cold.

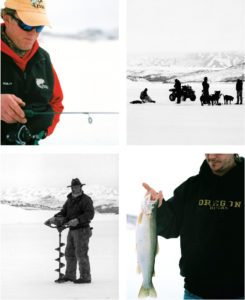

(Clockwise from top left) The spoils of the sport; Frank Smith affixes bait to his line; Paul Hopfenbeck’s golden retriever, Muti, patiently awaits the next catch; Johnny Christensen looks on as Hod Swanson augers into the ice.

Yet, at Magic Reservoir, quiet and isolation are rarities. On a sunny winter day with temperatures anywhere above zero, the ice bustles with people and dogs. Don Hartman, owner of West Magic Resort, a restaurant-cum-convenience store, reckons as many as 400 people will populate the ice on a good winter’s day.

They bring their fishing gear and their snowmobiles, their beer and hot toddies and sometimes even a gas-powered grill to cook mid-afternoon snacks. Some are in groups of two while others huddle among 15. They sip beer, watch their poles and take shelter from the wind in makeshift shanties.

Ice fishing is a communal activity, and it can feel more like a summertime barbeque or football tailgate than fishing trip. Ice fishing could also very well be a fly-fisher’s worst nightmare.

“Fly-fishing and ice fishing are entirely different activities,” says Hopfenbeck, who is a past president of Idaho Steelhead and Salmon Unlimited, a sport fishing group focused on recovering endangered stocks of Idaho salmon and steelhead. “It’s like backpacking by yourself in the wilderness versus having a barbeque in your backyard. Ice fishing is very, very social. People will have huge speakers and crank up their music. You could be two miles away and still hear them.”

(Clockwise from top left) Paul Hopfenbeck eyes the ice; Sportsmen exercise their right to assemble; Hod Swanson shows off the catch of the day; This Magic elder uses a powerauger to get through the reservoir ice.

It’s the serenity of it, and it’s the anticipation.” – Bill Tormey

Despite their penchant for watching the sunrise, Hopfenbeck and Tormey also revel in the chaos of a typical day on the ice. “It’s fun to be a part of the camaraderie,” says Tormey. “And everyone is having a good time and choosing to be outside instead of sitting in front of the television set.”

Tormey’s comment speaks to the duality of ice fishing: It is as much about friends’ company as it is about enjoying and culling dinner from the great outdoors.

Ice fishing season begins on Magic as soon as the weather turns cold and the ice begins to form. Fishers wait for it to thicken more than six inches, but impatience sometimes gets the best of them. There are times when the ice is still too thin.

Hopfenbeck describes the tentativeness with which fishers take to the ice in the early season. They remain close to the lake’s shores, unsure of their footing, not yet ready to trust nature’s work.

At Magic, the fish are often plentiful, and the fishing, once set up, can be rather easy. Before anglers relax and wait for a bite, they invest in their chosen patch of ice, sculpting it to fit their needs. They sweep snow aside, often with their boots. Then, using a hand or gas-powered auger, they drill a hole, usually eight inches in diameter, into the concrete-hard surface. The quickness with which a hole is created only confirms the fragility of the situation: It’s only a layer of frozen water protecting a man from the frigid depths below.

With holes drilled, a fisher will spend most of his day scrambling from hole to hole, clearing built-up slush or ice and checking on poles. Ice fishing is not a one-pole sport. One angler will have as many as six lines going in six different holes at once.

They fish with the bottom of their lines only a foot or so above the reservoir’s bottom. To know a line’s location in the water, a fisher relies on a combination of habit and intuition. With their hands alone, they can sense the slightest change, from where the bait is located to whether a fish is nibbling—no matter how deep.

While fly-fishers are finicky about their rods and flies, ice fishers are nonchalant. Poles are affordable and dispensable. It’s OK, for example, when one is pulled through a hole by a hungry fish. And bait is versatile. Fishers use anything from corn kernels to colorful marshmallows, favored for their buoyancy. Hopfenbeck and Tormey often bait their lines with night crawlers or the eyes of perch to catch more perch.

“What the fish are attracted to varies day to day,” says Hopfenbeck. “One thing will work one day, and then you’ll never get a bite the next.”

The catch at Magic is primarily perch and trout. Perch are iridescent little fish, gray on top with darker gray stripes running across their backs. Their bottoms are lighter, almost gold, with two bright orange fins. Tormey and Hopfenbeck say they particularly love to filet perch and often cook them while they’re still on the ice.

“You just drop them into hot water, and they curl up,” says Hopfenbeck. “Tastes like a little piece of lobster. Heat up some butter and dip it in.”

Johnny Christensen sits, waits and watches.

The two friends are also keen to the unique flavor of Magic trout. Trout in Magic feed on an indigenous fresh-water shrimp species that’s only found in the reservoir. The diet of shrimp makes the trout larger, fresher and pinker. Tormey claims it is some of the best trout he has ever tasted.

While trout are typically 10 to 12 inches long, some can be surprisingly large. In early 2009, Magic regular Ron Frey caught a seven-pound, three-ounce trout. Frey, whose license plates read “Fish Frey,” is famous on the ice for his success and dedication. When he’s not working as a bartender at the Silver Dollar Saloon in Bellevue, he can usually be found on the ice at Magic.

Magic Dam, which impounds Magic Reservoir at the northern edge of the Snake River Plain near the Clay Bank Hills and Rattlesnake Butte, was envisioned as early as 1901 and completed in 1910. The reservoir squats over the confluence of the Big Wood River and Camas Creek, the two waterways it captures. It’s about 30 miles south of Ketchum, and in the winter it invariabley freezes over.

When it was built, the dam was one of the largest of its kind and was designed to hold roughly 200,000 acre-feet of water, enough to irrigate downstream farms on the Snake River Plain in towns like Richfield, Gooding, Shoshone and Dietrich.

Fishing at Magic began as soon as the dam was complete. An excerpt from the Shoshone Journal, republished in the book, Idaho and the Magic Circle, reports that as early as 1914 fishers would travel to the reservoir and catch as many as 100 fish in a day, none shorter than a foot long.

Recreation flourished, and in 1936, the same year Sun Valley Resort opened, Ed Gleason opened the first “resort” at Magic. Called “Gleason’s Landing,” it became a center for weekenders who would build makeshift houses and cast the seasons through.

“Those who loved to fish loved the place, and it continued to grow, just a haphazard scatter of shacks,” wrote Betty Bever in Idaho and the Magic Circle. Eventually, however, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management decided the fishers who lived in shacks and shanties were “squatters” and auctioned the land. By 1959 as many as 125 houses, huts and cabins had been built on the west side of the reservoir.

The reservoir itself is large. Stretching for 14,000 acres when full, it is difficult to see exactly where it ends and begins. It also makes fellow ice fishers look like mere specks in the distance. The Soldier Mountains rise in the northwest, their snow-covered peaks a dramatic backdrop to the vast flatness of the reservoir’s surface.

Beyond crisp morning sunrises and warm camaraderie in a chilly-but-awesome setting, the economics of ice fishing are another reason for its popularity.

Hopfenbeck recalls taking his two sons and their friends out each weekend when they were younger. It was a safe place for the boys to play and learn the ins and outs of fishing. It was also far more affordable than buying a year-round ski pass for each son.

“For the blue-collar guy who can’t really afford to keep their kids on the hill all the time, it’s a great diversion,” says Hopfenbeck. “I’m not criticizing Sun Valley at all, but the reservoir is a place where they can yell and scream and go crazy and make a mess and have a great time.”

Hopfenbeck still takes his youngest son, 22-year-old Curtis Hopfenbeck, fishing each week. In January 2008, Curtis fell off a climbing wall at the Wood River YMCA and broke six vertebrae. While he is mobile, he’s still in recovery, and ice fishing is a low-impact sport he can do. It also allows Paul Hopfenbeck to spend time with his son.

“I bowl for him, and he goes ice fishing for me so that we can hang out,” Hopfenbeck says.

Hopfenbeck and Tormey both consider themselves conservationists. While Hopfenbeck reserves jabs for dams and reservoirs on the lower Snake River in eastern Washington, saying they block migrating salmon and steelhead on their journeys to and from the Pacific Ocean, he’s quick to point out that Magic Dam does not impede fish migration.

“The Magic Dam is simply an irrigation dam with some hydroelectric power,” he says. “Its water comes from the Big Wood River, which does not and never has had wild [salmon and steelhead] runs. It is an entirely different structure, and there is no conflict of interest.”

Introduced to hunting and fishing at a young age, Tormey shot his first deer at 16 and remembers weeping for days. Now a contractor sporting a big, bushy beard, Tormey has lived a few lives; he was trained as a professional chef at Baltimore’s International Culinary College. He still caters some, but is more interested in hunting and fishing for his own food than preparing meals for others.

“It makes you feel like you’re a part of the circle of life,” he says. “It is a very sacred act and demands that you be respectful for the animals that you harvest and the substance that they give you.”

After each kill, Tormey offers a prayer over the body of the animal. “Be it whatever God you may pray to, or maybe just the spirit of life that you’re acknowledging, it’s a kind of spiritual thing to take a life in order to sustain life.”

Hunters and fishers are hands-on conservationists, Tormey says. “In a sense, we’re stewards of the lands. Our dollars from hunting and fishing licenses and the tax on all the sporting equipment go into conservation.”

Tormey is right. Most of his $25.75 fishing license goes to Idaho Department of Fish and Game, which is unique among state wildlife management agencies because it relies primarily on its license and tag fees for revenue. It does not collect money from the state’s general tax fund.

According to Rob Morris, a senior conservation officer with the department, revenue from license sales goes to conservation efforts along with the maintenance and protection of public lands, which are used not only for fishing and hunting but also for bird watching and hiking. To Tormey’s way of thinking, it would be helpful if everyone had to buy a hunting or fishing license because almost everyone enjoys the benefits.

Though Hopfenbeck and Tormey rarely come up empty-handed, they are quick to point out that whether or not they catch anything really doesn’t matter.

“Ice fishing is about taking time out of your schedule,” Tormey says. “It’s the serenity of it, and it’s the anticipation.”

He then hesitates, trying to think of a better way to express himself.

“You know when you get the smell of sage, and your heart and head swell up, and it’s just that clarity of the moment, the crispness of being alive, of truly being alive in that moment?” he asks. “Fishing in general is a lot like that—the anticipation, the waiting, the fact that you never know when the fish will strike. It’s hard to put words to those types of emotions.”