A creekside spa in the mountains is a perfect place to soak in the wild geology of the Idaho sandbox. The water from the Frenchman’s Bend hot springs out Warm Springs Road west of Ketchum leaves the earth at 125 degrees Fahrenheit. While spring runoff can wash out such favorites—for a time—geological wonders have a way of enduring. When spring flows drop, enterprising bathers can rediscover the source of their pleasure—water superheated by the earth’s molten core.

Hot spring relaxation promotes a good attitude for contemplating complex geology. Hard as it is to conceptualize, the source of all that heat is the friction of tectonic plates colliding beneath Idaho. This colossal collision is also the cause of Idaho’s massive batholith lobes dominating central Idaho—rocks made from lava that cooled slowly underground. While soaking, one might also ponder the theory that many geologists subscribe to: that Idaho was once the coast of a supercontinent. There are fossils to prove it.

Go For A Drive

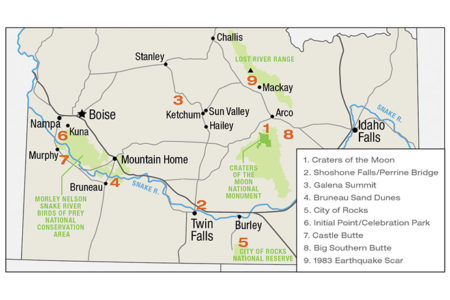

“You can learn a lot just driving around Idaho,” said Bill Bonnichsen, a career Idaho geologist, now in retirement. By way of example, Bonnichsen deftly explains the dynamics of basalt spatters at Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, and the older, denser, rhyolitic lava flows, which are the foundation of the spectacular Shoshone Falls near Twin Falls. Perhaps a surprise to many, these falls, just an hour from the Wood River Valley, are taller than the iconic Niagra Falls in New York.

“A lot of geology today happens indoors, but there are still chances to explore. I try to encourage young ladies and men to get out there and look at things,” said Bonnichsen.

The Snake River Plain and the Great Floods

The Perrine Bridge at the northern entrance to Twin Falls crosses the lumbering Snake River, which flows west through southern Idaho. The basis for the geology of the massive Snake River Plain surrounding the river is the Yellowstone hotspot that today triggers Old Faithful like clockwork. For 16 million years, as the North American plate has tracked southwest over the hotspot, the magma plume has littered the plain with volcanoes.

The scarring and building of eruptions prepared the land for the irrigated, now fertile, crescent-shaped landscape that has made Idaho famous for its potatoes. Long before human experiments with irrigation, Idaho was hit with epic floods caused by breaches of neighboring lakes Bonneville (Utah) and Missoula (Montana) 15,000 to 17,500 years ago as the glaciers retreated. The former, for example, is estimated to have released 15 million cubic-feet of water per second at its peak flow.

“The draining of Lake Bonneville left its mark when the impoundment broke at Portneuf (Narrows),” Bonnichsen said, adding that Missoula floods happened many times. Rocks from Montana can be found even in Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

Farther north, lakes were created by different but equally dramatic geological events. Lake Pend Oreille in northern Idaho was carved by glaciers retreating from Canada. It is now one of the deepest lakes in North America. Another huge body of water in the south, Lake Idaho, is long gone, but signs of all of these events are visible to the amateur earth scientist willing to take a closer look.

“Go to the Yellowstone area. There is a system of calderas (essentially sinkholes that form after rapid volcanic eruptions) stacked on each other,” Bonnichsen said. “As you go through the Snake River Plain, there is a whole series of supervolcanoes, the big rhyolitic eruptions.”

Sites off the Interstate

Bonnichsen emphasized the rewards of getting a highway map and getting off the interstate. He suggests gathering geologic maps of Idaho available through the Idaho Geological Survey with offices in Moscow, Boise and Pocatello. “There are landscapes that lay out the geologic underpinnings. If you go up to Galena Summit you get a good view south and north. You can see the Sawtooth Range, the White Cloud wilderness area. Stanley is a picturesque town. River running has become a popular way to learn about geology.” The Middle Fork of the Salmon carves right through the Idaho batholith and floating it provides an upclose view of this dramatic geology.

Roadside geologists can easily explore Bruneau or St. Anthony sand dunes left behind by the Bonneville Flood. These are other-wordly areas that have become not only geologic attractions, but also venues for new recreation, such as sand skiing and snowboarding.

Still other evidence of Idaho’s fiery past can be seen in ash layers where road cuts expose layers. Even a quick hike to Hulls Gulch Reserve in Boise will reveal ancient wonders.

The Craters of the Moon basalt spatters beckon beyond Carey; some are only 2,000 years old, which makes Idaho literally action-packed as far as geologic time scales go.

Some of the granite spires at City of Rocks are upwards of 2.5 billion years old. Photo by Glen Oakley

Twin Sisters, granite spires at the City of Rocks in southeastern Idaho, was a crossroads for pioneers. They are protected as part of the California National Historic Trail “viewshed.” Side by side, the 28-million-year-old Almo Pluton granite of the north feature is a youngster compared to the south spire, a 600-foot-tall feature of 2.5-billion-year-old Green Creek Complex granite, some of the oldest exposed rock on the planet.

Compare that to a human geological site of sorts: Initial Point, the 1867 survey point reset in 2008 on BLM land south of Kuna. It is the reference point for all survey work in Idaho. It is a highpoint in the washout of Lake Bonneville. The tiny survey marker is the legal basis for Idaho’s private property boundaries.

Today, Initial Point is a paved drive from Boise, a waypoint en route to Celebration Park on the Snake River near the Nelson Conservation Area to see car-sized melon gravel basalt boulders left behind in the flood’s wake. Viewed through the lens of geologic time, the notion that one’s property or favorite hotspot will remain as is in perpetuity is wild at best. The earth is not the solid sphere it seems to be from the front door or even from space.

Bonnichsen also recommends other off-interstate sites south of Boise toward Mountain Home and over to Nampa. Many volcanoes are easily visible: places like Castle Butte between Grandview and Murphy. In addition to the hundreds of volcanoes in the Snake River system, once the eye is trained, basalt eruptions spring up well beyond Craters of the Moon.

“There are some interesting things to see by Arco, too,” Bonnichsen said. “To the north, there’s the Lost River Range limestone.” East of the town—the first nuclear-powered city-—at 300,000 years old, Big Southern Butte is the largest and youngest of three rhyolitic domes that formed over a million years ago but never erupted to spread lava and ash in typical volcano fashion. The volcanic dome kept its top and rises about 2,500 vertical feet, east of Craters of the Moon, south of Howe, Idaho, and west of the Idaho National Laboratory. The butte is reportedly one of the largest volcanic domes on earth.

Anyone trying to understand how the two-dimensional map of the Gem State got so crinkled in 3-D can spend a lifetime testing the theories. That’s exactly what the dynamic Moscow geology duo Bonnichsen and his wife Marty Godchaux have done, and they provide thorough interpretation via Idaho Public Television (Visit idahoptv.org/outdoors/shows/geology/).

The key to unlocking Idaho’s challenging geologic story, which has had essentially nothing to do with people, at least until the start of the Anthropocene that started at the end of the last ice age 10,000 years ago, is to find some friends, places where hot water meets rock, and relax into the study. The inconceivable timeline of earth’s geologic history could make for incredible stop-motion animation.

The Great Crack

Kirkham Hot Springs

For the latest drama of subduction and uplift, check out the 1983 Borah earthquake that created the 23-mile-long crack in the Lost River Range.

“The scarp of that event is still visible and there’s an information stand,” Bonnichsen said. “(In nearby) Challis you intersect with the Salmon River again. It’s got its own canyon and a variety of volcanic rocks and exposed lake beds.”

All of it is just a short drive over Trail Creek from Sun Valley. However, amateur geologists with noses to the grindstone might take a week just to get there.

And so it goes for exploring the geology of Idaho: the breadth and depth of the adventure is solely up to the explorer. The complexity and grandness of the state’s geology lends itself to a lifetime of discovery, or perhaps just a summer afternoon of driving about.