Literally and figuratively, Levi Smiley was not alone. As he led a group of pioneering prospectors into the Sawtooth Mountains in the spring of 1878, thousands of other men like Smiley were adventuring into the most rugged and remote reaches of the Rocky Mountain range. And the focus of their endeavors was one and the same.

Gold.

But discovering the quartzite veins which were home to lodes of the precious metal—in addition to silver, copper, zinc, tungsten and lead—wasn’t the only return they hoped to garner through their herculean effort. The gold diggers of the time also thirsted for adventure and the desire to live a life defined by hard work, freedom of movement and the single word that is perhaps the most emblematic of the time: Eureka!

Once miners had discovered a promising find of the appropriate geology, their next move was to file a mining claim on the land, a legal protection codified in the General Mining Act of 1872. Claims were generally filed at the county courthouse, often a perilous journey in itself, and recorded, so that redundancy was avoided, a public record of patented and unpatented claims was established and the occurrence of gunfights over the rights to dig was minimized.

Generally speaking, the system worked well and remains in place today. However, in the modern-day world, breaking one’s back for the promise of precious metals has become primarily a hobby endeavor for those with a desire to reconnect to their pioneer impulses or spend retirements panning for the odd gold flake while enjoying the privacy and natural beauty of the surrounding wilderness.

In many cases, the mining claims of today are being used by their owners for purposes utterly disconnected from the prospecting roots that led to their establishment. These petite islands of private land are now utilized as personal refuges, basecamps for recreational endeavors or maintained as a continuation of a family’s connections with the land and industry that helped to define their identity for generations. As a result, this evolution of use begs the question: in the modern day, what is the value of a mining claim?

Cory Smith, owner of Wintertux claim. Photo by Kirsten Schultz

“I find it to be priceless,” said Cory Smith, partner in the Sunbeam and Pride of the West claims nestled in central Idaho’s Sawtooth mountains not far from where Levi Smiley and his gang originally set up shop. “It’s pretty all the time. I can be there in 45 minutes from Ketchum and then am totally secluded. It’s a summer camp feeling.”

But Smith’s connection to the claims goes beyond a “let’s go play in the woods” mentality. “There is a pride of ownership,” Smith stated genuinely. “You want to improve the land around it and make it a better place.” Smith’s father was the mill foreman at the local mine in his original hometown of Silverton, Colorado.

Smith’s claim, known now as Wintertux, boasts a sturdy, recently constructed log cabin built from the surrounding Douglas fir that blankets much of the mountainsides. A small alpine stream meanders past the rustic edifice and wildflowers grow ubiquitously throughout the summer months before the August freeze sets in at the 8000-foot elevation. An old mill site resides nearby and many other claims pepper proximal drainages.

Smith, his business partner Scott Robinson and their friends use Wintertux as a base-camp for backcountry skiing adventures in the winter and mountain biking in the summer. Though originally developed for mining the rich ore beneath the mountains, the claim now serves as a headquarters to mine the powder and corn snow that falls upon the surrounding peaks.

Mine entrance at Wintertux. Photo courtesy Cory Smith

Wintertux is a combination of patented mining claims. Patented claims are mining claims that were filed in a manner that results in the private property rights being transferred from the U.S. government to a private individual or entity. If your claim is patented, you own the dirt. Unpatented claims allow mineral recovery rights to the claimant but do not include the rights associated with private land ownership.

In 1994, during the first Clinton administration, the process of patenting claims was discontinued, but existing patented claims retained their private land standing and were thus grandfathered in. This law remains in effect, though the current or any future administration could overturn it. Therefore, patented claims are a limited commodity and can bring a hefty sum to the sellers of such private land.

Concurrent with Smiley’s 1878 sojourn was an uprising of Native Americans in a sparsely inhabited prairie 40 miles to the south. When a courier alerted Smiley and his gang of the beginnings of what would later be referred to as the Bannock War of the Camas Prairie, the mining camp disassembled and headed for perceived safer ground in Challis, 50 miles to the northeast.

Mining had many challenges in those days and, at that time, the wilds had native human populations roaming them, not all of whom received the miners in a kindly fashion. The following year, Smiley nevertheless returned to stake more claims and soon the communities of Sawtooth City and Vienna (pronounced Vy-ee-nah) sprung up.

Sawtooth City was located approximately 3 miles west of a conglomeration of summer homes, which today is referred to by the same name. The boomtown grew to a population of 250 by 1881. Vienna, at its height, featured some 250 buildings, including 14 saloons, six restaurants, three general merchandise stores, a Chinese laundry and blacksmiths’ shops. The two towns maintained a heated rivalry that was often expressed through fisticuffs and other more violent conflagrations.

By 1887, the silver deposits that had drawn Smiley and those who followed were essentially played out and by the end of the First World War there was little sign that the towns had ever existed except for broken glass, a weathered cemetery and a few decrepit mining artifacts strewn throughout the flowered valleys.

The boom, as is the history of so many mining encampments, had gone bust.

In 1873, a few years prior to the development of the original Sawtooth City and Vienna, a pioneer from New Brunswick found himself with shovel in hand standing on the bank of Jordan Creek up the Yankee Fork drainage of the Upper Salmon River. John G. Morrison had traveled long and far to reach his personal Shangri-la. When he discovered a respectable lode of ore, he immediately sent word for his five nephews to join him from eastern Canada.

The Steen brothers were of Scottish and Irish heritage, as were many pioneers of that day. They were accustomed to hard work and arrived ready to dig. After working on Jordan Creek for several years, the family purchased the Yellow Jacket mine, a short distance to the northeast in 1888. This mine, once boasting a 60-stamp mill—the largest in the country at the time—became a vibrant backcountry boomtown and is owned by the Steen family to this very day.

Alison French Steen, together with her sister and two cousins, now oversees the operations of the family-owned corporation, though mining operations ceased decades ago. Alison maintains the property while cousin Lori, a resident of Corona Del Mar, California, provides additional administrative and financial support.

The Yellow Jacket Mine today. Photo courtesy Allison Steen

The Yellow Jacket is an excellent example of a patented claim that has remained with its owners for generations even though active mining has long since faded from the equation. “There was return in the early days, but, otherwise, it was primarily a bust,” Alison Steen noted as she perused old family photographs on her antique kitchen table.

“It was all about speculation and acquisition then. That’s where the money was made. The old man with the gold pan is a very brief chapter in the history of most mines as the buying and selling of claims was the real business in those days,” Steen offered.

“The Yellow Jacket has cost a life in every Steen generation,” Steen reminisced. “Silicosis (black lung disease), mining accidents, dedication to a mine that didn’t produce enough return to be profitable. But it’s what I know. I grew up on it.”

When asked how many generations of her family have been connected to Idaho and the Yellow Jacket mine, she began to count fingertip to fingertip. Shortly, she moved to extend the fingers of her second hand. “Seven,” she proudly reported. “There are still multi-generational families with patented claims in the backcountry. Families have hung on for generations,” she continued. “There is a strong and lasting tradition, an inseverable connection to the land regardless of how far away people move or how much time passes.”

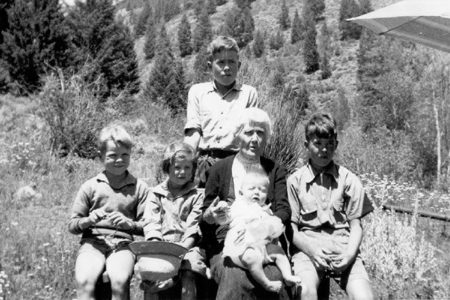

Seven generations of the Steen family have been connected to Idaho and the Yellow Jacket mine, including Granny French, seen here with five great grandchildren.

Steen smiled as she recounted the stories of her grandmother and great-grandmother, Harriet French Steen and Catherine French. “Eventually, as each woman grew older, they ultimately moved to Southern California to live with family once they were too far along to maintain the mine.” On multiple occasions over the years, each went missing. “Inevitably, they were found at Yellow Jacket, gardening or tidying up, some 800 miles from home,” Steen laughed. “It’s where they wanted to be.”

As far as the future of Yellow Jacket is concerned, Steen expects her 11-year-old daughter, A.J. (short for Annie-Mae June), eventually to take the reins based on a clear interest in and passion for the mine. “Many of the other members of my family didn’t have the taste for the lifestyle the way my dad did, the way I do, the way my daughter does. Eventually, she’ll be the one to carry on the tradition.”

Though the pioneering days of Levi Smiley and his contemporaries are long past, even today deep connections exist between the mining claims of central Idaho and their stewards. Dotted throughout our surrounding mountains, some in the valleys that drain them and some on the summits themselves, privately owned islands of tailings, mine shafts, rusting machinery and an intense and rugged beauty supply their owners with a variety of purposes and uses.

In each of these various situations, a common connection to an important chapter of Idaho’s human history exists, a volume that still provides varying value to the owners and an immediate, direct connection to their storied and pioneer pasts.