From Left to Right: When this rogue horse fled the herd during the roundup, a BLM helicopter hovered close for upwards of ten minutes to drive it to the corral; The mare seen here was featured in SVM’s Winter 2007 issue; The stallion seen here in 2006 displayed far different language in BLM holding corrals

There’s a dustup in the sage-covered hills of central Idaho. Wild horses, a fixture on the landscape for decades, are at the center of a struggle as old as the West itself, an argument between the federal government and the people who call this harsh land their home. The animals caught in the middle are, as usual, innocent to the trouble that surrounds them.

And because this is a modern take on an old story, it starts with a photograph. Well composed and powerful, it changed the lives of three Sun Valley-area women and 19 wild horses.The photo captured a wild mare and stallion in a sentimental moment, holding their soft noses together through the hard metal frame of a rangeland corral. They were about to be forever separated.

Doro Lohmann, a Hailey-based horse trainer and founder of Silent Voices Equine Horse Rescue, sought out the photographer, Elissa Kline, after viewing the image. “I told her, ‘I want to do something so I can sleep at night,’” Lohmann said.

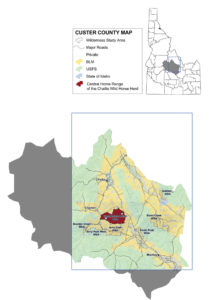

The photograph was taken following the July 2009 roundup of 366 wild horses on U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) public range near Challis, Idaho. Such roundups, says the BLM, are necessary to control expanding populations of a non-native wild species. Such roundups, say wild horse activists, are cruel and unnecessary and run contrary to the spirit of a federal law designed specifically to protect the herds.

Wild horse roundups—always fast-paced, sometimes violent and often controversial—are the reason the three women united, and Kline’s emotive photography is the thread that stitched them together.

Jodi Herlich, a volunteer with the Animal Shelter of the Wood River Valley and manager of Ketchum’s Jensen Stern jewelry store, launched a letter-writing campaign in 2008 after Kline showed her photos of the horrors of an earlier roundup. When the BLM postponed a roundup that summer, Herlich attributed the decision to her grassroots effort. “I had a huge response,” she said. “People [copied] me on letters they wrote to their senators and congressmen. They were so heartfelt. It’s an issue that touches us on a core level,” she said.

First Encounters

Kline first visited the Challis herd after a 2004 BLM roundup horrified her friend and Challis area homeowner, Bonnie Garman. Kline was working as a ranch manager near Clayton, a pinprick of a town about 20 miles southwest of Challis, and said her friend’s “passion and horror” drew her in. After that first meeting she returned to the herd time and again.

“I probably photographed 150 horses over the course of five years,” she said. “They were thriving. Their hooves were strong. They were beautiful beyond words. I’d see the same families season after season, year after year, and they were still together.” To familiarize herself with the herd, she established a routine, always wearing the same jacket and hat and keeping a respectful distance.

“I would talk to them and tell them, ‘I’m not going to hurt you. Maybe I can help you stay on the land,’” she said. “That was my goal, to bring more public awareness to their plight.”

Kline had a bold vision for her photos: silk-screen them onto seven-foot fabric panels. Hung in the middle of a gallery space, Kline recreated the cherished herd as a life-size installation. She hoped people would walk among them and feel their power and beauty.

Shown first at the Sun Valley Center for the Arts in 2006, the exhibit, “Herd but not Seen,” has since been exhibited at venues in four Western states and during talks she’s given alongside Deanne Stillman, author of Mustang: The Saga of the Wild Horse in the American West.

While she reached hundreds through her exhibition, the powers she wished to influence carried on. In July 2009, despite citizen protests, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management returned to Challis for another roundup.

A Brief Horse History

People who grow up around horses have it in their blood for the remainder of their days. The smell of a horse is like bottled nostalgia. For others, the mustang is an undying symbol of a free America.

But wild horses are not endemic to the American West. They did not evolve with the present-day ecosystem, and their likely ancestors went extinct in North America more than 10,000 years ago.

In southwest Idaho, the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument memorializes the highest concentrations of prehistoric horse fossils in North America. The park includes 550 fossil sites where more than 200 Hagerman horse fossils were unearthed.

Despite its name, Idaho’s ancient horse is probably more closely related to the zebra, writes the Hagerman Monument’s paleontologist Greg McDonald in his paper, Hagerman “Horse”–Equus simplicidens. It’s commonly accepted science that the Hagerman horse, the closest ancestor to the modern horse, went extinct in North America, but that some of the animals may have migrated to Asia before dying out on our own continent. Idaho was a vastly different place during the height of the Hagerman horse’s inhabitation, the late Pliocene. The fossil record at Hagerman shows a savannah-like environment that may have received 20 inches of rain a year—double today’s average.

Challis’ wild horses did not evolve with the sagebrush steppe ecosystem that now dominates Idaho’s high desert. It was tens of thousands of years after Idaho’s prehistoric horse went extinct that its possible progeny—modern horses—returned to the continent carrying European explorers on their backs.

Today, the Challis herd is Idaho’s largest and numbered as high as 660 prior to 1978, when the BLM won a court battle to whittle the population down to 250, according to Lisa Dines, author of The American Mustang Guidebook. The population continues to fluctuate from year to year as roundups, which the government calls “gathers,” continue. Challis’s drama is an isolated chapter in a saga being written throughout the American West.

In the 1950s, Nevada animal rights activist Velma Johnston brought the issue onto the national stage. After learning of the ruthless methods used to gather wild horses (to then sell for meat for dog food or human consumption in Europe), Johnston led a grassroots campaign comprised mostly of school children. News of the roundups and slaughters outraged the public, and in 1959 Congress passed a law forbidding the hunting of wild horses from motorized vehicles and airplanes, but it fell short of the protections Johnston envisioned.

In December 1971, with public outcry unabated, Congress passed the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act, a law that called for more thorough “management, protection and control” of the animals. The law also established an adoption program for willing citizens and a euthanasia program for old and sick animals.

The law said, “Congress finds and declares that wild free-roaming horses and burros are living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West; that they contribute to the diversity of life forms within the Nation and enrich the lives of the American people.” The law prohibits their capture, branding, harassment or killing. They are to be considered an “integral part of the natural system of the public lands.”

The law addressed the public’s concerns and, in the process, created a new set of problems. With the new protections in place—and no natural predators—wild horse populations climbed. The law was amended, and government roundups—complete with low-flying chase helicopters and terrified horses fleeing them in full-gallop—became more frequent. Today, the decades’-old issue is again a lightning rod for animal activists and public land managers alike.

A National Issue

Since the 1971 bill was passed into law, roughly 300,000 wild horses have been adopted nationwide, said BLM Idaho State Director Tom Dyer in an October interview. “We do have horses in long-term holding, but every year we try to come up with new solutions,” he said. “The desire is to maintain a balance without a serious impact to the range, or the animals themselves, without gathering. That’s one of our goals for the future.”

The BLM wants no more than 253 wild horses in the Challis zone. The July 2009 roundup gathered 366 horses and re-released 155. Eleven died in the process.

“There is a certain amount of mortality in the roundup. It’s traumatic,” Dyer conceded.

In the past two years, 255 wild horses died in roundups throughout the West. For the July roundup in Challis, Kline toted video and still cameras back to the familiar sagebrush hills as a small helicopter chased the horses—often flying within feet of the frightened animals—into holding pens.

“This was happening to them,” she explained. “The least I could do was document it. I knew it would be tough, but I had no idea how hard and how bad.”

For her documentary on the roundup, Kline interviewed Kenny Bradshaw, an 87-year-old rancher who has lived his whole life in and around Challis. He gave a powerful testimonial. In the slow twang of an old rancher, Bradshaw said there was no reason to take those horses off the range. “There’s plenty of feed for both horses and cattle. They weren’t hurting anyone. This is just a bad deal, and I don’t like it one bit.”

The issue has lawmakers’ attention. A rider attached to a bill by former U.S. Senator Conrad Burns, R-Montana, in 2004, proposed rewriting the more than 30-year-old Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burro Act. Burns proposed that wild horses over the age of 10, or those that had been unsuccessfully offered for adoption three times, could be sold “without limitations” to the highest bidder. The failed measure would have opened the slaughterhouse door.

In October, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar proposed moving some herds from their home ranges to holding facilities, renamed “refuges,” in the Midwest and East. Citing a recent decline in the number of wild horses and burros being adopted because of the economic downturn, Salazar said the BLM maintains nearly 32,000 wild horses and burros in holding, including more than 9,500 in expensive, short-term corrals. In 2009, the program cost the government $29 million.

Salazar, in an October letter to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, maintained that the status quo is “not sustainable for the animals, the environment, or the taxpayer.” The relocation plan, he wrote, would “enhance the conservation for this iconic animal and provide better value for the taxpayer.”

Following Salazar’s announcement, an alliance of more than 60 organizations called for suspension of all wild horse gathers in the United States. The Equine Welfare Alliance called for an immediate moratorium by all government agencies.

Grassroots Innovation

After the July 2009 roundup, Herlich, Kline and Lohmann took action on a local level. Lohmann found a ranch for the adopted horses to roam. Kline maintained communications with the BLM. And Herlich wrote letters seeking funding. “We fell into our places, and we have gotten quite a nice response from people who care,” Herlich said.

Lohmann’s nonprofit, Silent Voices, had established a solid track record of saving and advocating for mistreated domestic horses and, in an unprecedented move last October, the BLM permitted her to adopt 19 wild mares (the 1971 law had capped adoptions at four horses per citizen). Before Lohmann stepped in, the mares had been held captive for four months and were scheduled to be shipped to a holding facility in Oklahoma.

“We can go out and bitch about it, or we can create a format that will work for the horses, and include the BLM,” Lohmann said. The mares, now living here in the southern Wood River Valley, were transported by the BLM in mid-October.

“I think they know they are safe, and I think they know they won’t be harmed anymore, and they also know they will never go back home,” she said. “They seem confused about how to interact with each other properly, lacking a functioning family dynamic. They are broken, some of them deeply sad and lost, but they are hopeful.”

By late-fall, the horses began establishing small groups even though none belonged to the same herd in the wild.

The white mare, that Lohmann first saw nosing its mate through the fence in Kline’s photograph, is here as well. Lohmann is still drawn to her and, at one point, the mare to Lohmann.

“She allowed me to feed her hay and touch her face,” Lohmann said. “She is the only one I have named: Sabia, ‘the wise one.’ I believe that this mare had reached out to us and talked to me. She had managed to make a connection with me, and that is what brought all the mares to us.”

And here the mares live for the time being, almost, but not quite, wild.