Looking across at Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains and the headwaters of the Salmon River from Galena Summit, Ernest Hemingway once said to a hunting companion, “You’d have to come from a test tube and think like a machine to not engrave all of this in your head so that you never lose it.” This comment, as reported by Lloyd Arnold in “Hemingway: High on the Wild,” was unknowingly prescient. A machine—the electroconvulsive therapy machine used to treat Hemingway’ depression late in life—would contribute to his inability to recall events, to think, and, consequently, to write fiction in his final years at Sun Valley. That fact notwithstanding, Hemingway’s comment captures his love for the Idaho wilderness, remote frontiers, and intact ecosystems.

Hemingway was not an environmentalist, as the term is defined today, for he did not act to preserve wild places and the wild animals much beyond his desire to visit intact, frontier ecosystems in which to hunt or fish. But his passion for wilderness lives on in his family and in the land use policies affecting the mountains, rivers, and streams of central Idaho. Hemingway always sought out frontiers where wild animals flourished and the local people were in touch with the land. Hemingway scholar Marty Peterson has stated, “I think (Hemingway) was in search of the vanishing frontier. I think he was in search of a place where he could have some anonymity, where the hunting and fishing was still good. And he found that in central Idaho.”

Hemingway had a deep appreciation for the natural world and was a keen observer of nature. Moreover, Hemingway’s impact on his first son, Jack, led to the preservation of Silver Creek—a beautiful trophy trout stream where Hemingway hunted and fished—his beloved view of the Boulder Mountains from his Ketchum home led to the naming of the “Hemingway-Boulders Wilderness,” and as the author of the most important description of “catch and release” in literature in his story “Big Two Hearted River,” Hemingway would be pleased to know that much of the Big Wood River is now “catch and release.”

Hemingway valued the wildness that a frontier existence provided. Whether it was marlin fishing off of Key West and his beloved Cuba in the vast wilderness of the sea, backcountry skiing in the mountain wilderness of the European Alps, big game hunting in the wilds of Africa, or waterfowl, pronghorn, and deer hunting in the wilderness of central Idaho, Hemingway loved the awe-inspiring feeling of participating in the intact ecosystems of wild places. His heroic characters in his stories and novels viewed nature as an arena upon which to project one’s ethical code through the act of hunting or fishing. Hemingway’s evolving views of and practices in nature throughout his lifetime and writings reflect his reactions to man’s detrimental impact upon nature. And his continuing legacy in Idaho is deeply connected to wild places he loved and that are now preserved.

Hemingway’s Wild Idaho

In the fall of 1939, Hemingway was provided free room and board in exchange for use of photographs of Hemingway hunting and fishing in the Sun Valley area. Write, hunt, fish, pose for a few pics, and live and eat carte blanche. Sounded just fine to Hemingway who needed time to work on his Spanish Civil War novel, “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” During his visits to Sun Valley, Hemingway valued the influence of the local hunting guides’ knowledge of the wildlife in the Wood River Valley, Pahsimeroi Valley, and along the Middle Fork of the Salmon River.

In the video memoir “Hemingway in the Autumn,” the late, local hunting guide and rancher Bud Purdy recalled a jump shoot with Hemingway on the Little Wood River near Carey, Idaho. “Three mallards flushed in a small ribbon of a side stream on the Little Wood River. As they flushed, Ernest got all three ducks with three pulls. Bang, bang, bang and the three ducks fell. You could have given him a million dollars and he would not have been any happier.” Hemingway valued the pristine wetland habitat of Silver Creek and the Little Wood and loved the unparalleled duck hunting close to the comforts of free room and board at the Sun Valley Lodge. Having written a few chapters of “For Whom the Bell Tolls” that day, he finished it off with his other great skill: shooting birds on the wing.

In addition to finding a place of unparalleled hunting in the Wood River Valley, Hemingway also found like minded individuals who appreciated his deep knowledge of wild animals. In a 2000 interview, Ketchum local Anita Gray remembered a duck hunt with Hemingway on Silver Creek. As they were walking along a gin-clear tributary to Silver Creek, Hemingway noticed bobcat tracks. “He showed me the larger (bobcat) tracks and the smaller (bobcat tracks) and then pheasant tracks,” recalled Gray. “He said, ‘she taught the cub how to kill a bird.’ He could read it all in the tracks.”

Hemingway’s respect for how nature works and the mentoring of the young cub is evident here and is often lost in the iconic images of Hemingway with his trophy kills during African safaris. Hemingway scholar Susan Beegel notes in “Ernest Hemingway in Context,” “(Hemingway) had a Darwinian view of animals in competition, but little understanding of cooperative relationships among species.”

While ecology had yet to be a science frequently applied to habitat restoration, wilderness preservation, and species protection in his lifetime, Hemingway reveals in this moment that he viewed himself as a hunter able to enter into the predator-prey competition in nature. He expresses an appreciation for natural processes, in this case the mentorship of a mother bobcat in training her cub to hunt. During his hunts on Silver Creek and in the pheasant-flush fields of Shoshone and Dietrich, Hemingway loved being a mentor to novice hunters, particularly his new love at that time and the woman who would become his third wife, Martha Gellhorn.

Hemingway’s Wild Moments in ‘In Our Time’

This respect for the life and death, predator-prey relationships exhibited in local stories also manifests itself in Nick Adams’ experiences fly fishing for trout in northern Michigan in Hemingway’s short story collection “In Our Time.” The fictional character Nick Adams fly fishes in “Big Two Hearted River I and II” for trout on a solo journey in search of the former innocence he once had fly fishing with his dad and Uncle George before experiencing the horrors of World War I (WWI).

It is important to note that the town of the story, Seney, Michigan, and the surrounding forest, are burned down by unregulated clear-cutting practices and the burning of the slash. As Debra Moddelmog writes in “Ernest Hemingway in Context,” by 1907, “… more than 10.7 million acres of the state had been clear cut” and “the state was periodically swept by devastating fires.” Neither is it possible for Nick to regain his youthful innocence after witnessing the carnage of WWI, nor to return to the pristine woods and unpolluted streams of Hemingway’s youth in Michigan. This, in part, informed Hemingway’s appreciation of the clear and clean Big Wood River and Silver Creek, as well as the virgin forests of Salmon River country.

After Nick Adams collects some fire-charred black grasshoppers in “Big Two Hearted River,” he catches a few trout that he keeps for dinner and then catches and releases a trout. Both moments of killing and cleaning the trout for dinner and the releasing of the trout provide an interesting insight into Hemingway’s relationship with nature and foreshadow his evolving views on man’s interaction with the natural world. Describing the moment of killing and cleaning the trout, Hemingway writes:

He took out his knife, opened it and stuck it in the log. Holding (the trout) near the tail, hard to hold, alive, in his hand, he whacked him against the log. The trout quivered, rigid. Nick laid him on the log in the shade and broke the neck of the other fish the same way. He laid them side by side on the log. They were fine trout. Nick cleaned them, slitting them from the vent to the tip of the jaw. All the insides and the gills and tongue came out in one piece. They were both males; long grey-white strips of milt, smooth and clean. All the insides clean and compact, coming out all together. Nick tossed the offal ashore for the minks to find.

Nick effortlessly and efficiently kills the trout humanely and cleans it. The “whacking” of the trout’s head and “breaking of its neck” against the log kills the trout instantly, for the “trout quivered” and then went instantly “rigid.” Moreover, the tossing of the trout’s entrails—the “offal”—to the shore “for the minks to find” reflects Nick’s concern that all of trout be eaten and that other members of the ecosystem benefit from his taking.

This is the beginning of Nick’s transformation from a mentally damaged WWI veteran to a man who is able to control his actions according to an unspoken code and heal himself by participating in the natural world. Nick positively influences his natural surroundings: a river and forest that have been adversely affected by reckless, unsustainable practices of clear cutting and the burning of stumps and slash.

Nick values nature, and this is demonstrated in the story when he catches and releases a trout while fly fishing. Knowing that he has enough trout for his dinner, Nick takes precautions in order to avoid unneeded harm and death to the trout he will not eat. Describing the process of Nick landing a rainbow trout in the fast moving riffles of the river, Hemingway writes:

Nick stooped, dipping his right hand into the current. He held the trout, never still,

with his moist right hand, while he unhooked the barb from his mouth, then dropped him back into the stream. He had wet his hand before he touched the trout, so he would not disturb the delicate mucus that covered him. If a trout was touched with a dry hand, a white fungus attacked the unprotected spot. Years before when he had fished crowded streams, with fly fishermen ahead of him and behind him, Nick had again and again come on dead trout, furry with white fungus, drifted against a rock, or floating belly up in some pool. Nick did not like to fish with other men on the river. Unless they were of your party, they spoiled it.

In the context of Nick’s dejected state of mind after the war, it should be noted that Nick admires any creature that has a protective barrier to ward off disease—physical or psychological. He does not want to contribute to unnecessary harm in the world and, particularly, in the once pristine woods and rivers of his youth. The “other” fishermen on previous fishing trips—who do not follow the unspoken code of how to catch and release properly—violate the fishing code and cause unnecessary death, something Nick has seen too much of at war.

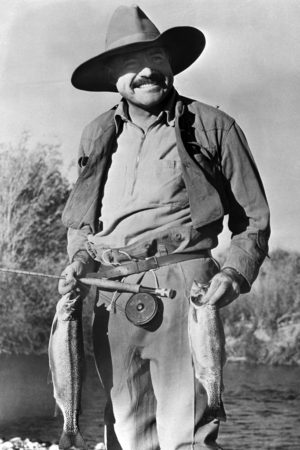

Hemingway fishing in Idaho. © Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images

Hemingway would be pleased to know that most of the Wood River Valley’s Big Wood River and Silver Creek are now “catch and release, fly fishing only” streams that are closed to fishing in the months of April and May when trout are spawning.

Hemingway’s view of nature was primarily shaped by a Progressive-era, Roosevelt conservationist view. Like President Teddy Roosevelt, who set aside large tracts of land for the utilitarian reason of preserving the quality of hunting in these areas, Hemingway valued the intact ecosystems of central Idaho for the quality of the hunting and fishing they provided. As one of the first literary writers to depict catch-and-release fishing and as vice president of the International Game Fish Association, advocated and practiced catch-and-release marlin fishing and argued for a closed season on marlin fishing during the spawning season, Hemingway would be encouraged to know that these practices took hold in the wild country he so loved in and around Sun Valley.

Hemingway’s views of policies affecting nature evolved over his lifetime and, interestingly, were enacted in both policy and action by his first son, Jack Hemingway. Jack picked up his dad’s lead and, like his father who led the International Game Fish Association, Jack became Idaho’s Fish and Game Commissioner. In this role, he was integral to The Nature Conservancy’s purchasing of the Silver Creek Preserve and the nearby easements established with local ranch owners. Jack was also an advocate of the catch-and-release, fly-fishing-only policies that govern Silver Creek Preserve.

While Ernest Hemingway was shaped by the Roosevelt-Pinchot conservationist mindset, son Jack came to the idea—in belief and practice—that nature and its inhabitants have an intrinsic right to exist. Further, he felt that current and future generations have an equal right to enjoy intact ecosystems. It took the practical actions of son Jack Hemingway to realize his father’s nascent environmental consciousness. Jack also followed his father’s lead to war, jumping out of airplanes during World War II into conflict areas with fly rod and gun, just in case he came upon a German trout stream with a little time on his hands.

The Hemingway Silver Creek Legacy memorial is a rock that bears the epigraph to “The Sun Also Rises,” excerpted from Ecclesiastes: “One generation passes away, and another generation comes. But the earth abides forever. The sun also rises, and the sun goes down, and hastens to its place where it arose.”

After Hemingway’s 1961 death in Ketchum, Idaho, son Jack ensured that “the earth abides forever,” by allowing the remarkable wildlife diversity of Silver Creek to remain intact for this and future generations of moose, ducks, deer, elk, trout, and people. In addition, Ernest Hemingway would be pleased to know that the wild, but unregulated, mountains of central Idaho have been protected in perpetuity by the recent federal designation of three wilderness areas in a state that ranks third in total wilderness acreage (behind Alaska and California). The Sawtooth Mountains Ernest Hemingway so admired from Galena Summit in 1940 became a wilderness area in 1972. The Middle Fork of the Salmon area that Hemingway hunted became the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness area in 1980. And, most recently, the Boulder-White Cloud mountains—the peaks Hemingway could see from the deck of his Ketchum home—became part of three wilderness areas in 2015.

Since son Jack was so heavily involved in the preservation of the Silver Creek Preserve with The Nature Conservancy, Mary Hemingway (Ernest’s fourth and final wife) bequeathed the Hemingway House in Ketchum to The Nature Conservancy. The Community Library of Ketchum now oversees the house as part of the Hemingway Legacy Initiative.

The property has been largely untouched since Mary’s passing in 1986; the 14 acres of Big Wood River riparian area on the Hemingway property are an enduring legacy to the river, trout, ducks, elk, and deer Ernest loved so much. The Hemingways still contribute to the wild frontier we all share and love in the Wood River Valley.