High School: Sun Valley Community School

Post-Graduation Plans: Attending U.C., Berkeley

Nelson Mandela once said, “The only assurance an African orphan has, without education … is death.” Simply put, if an African orphan does not obtain an education, they will not have the ability to escape the poverty in which they exist and their lifespan will likely be far shorter than that of an average person.

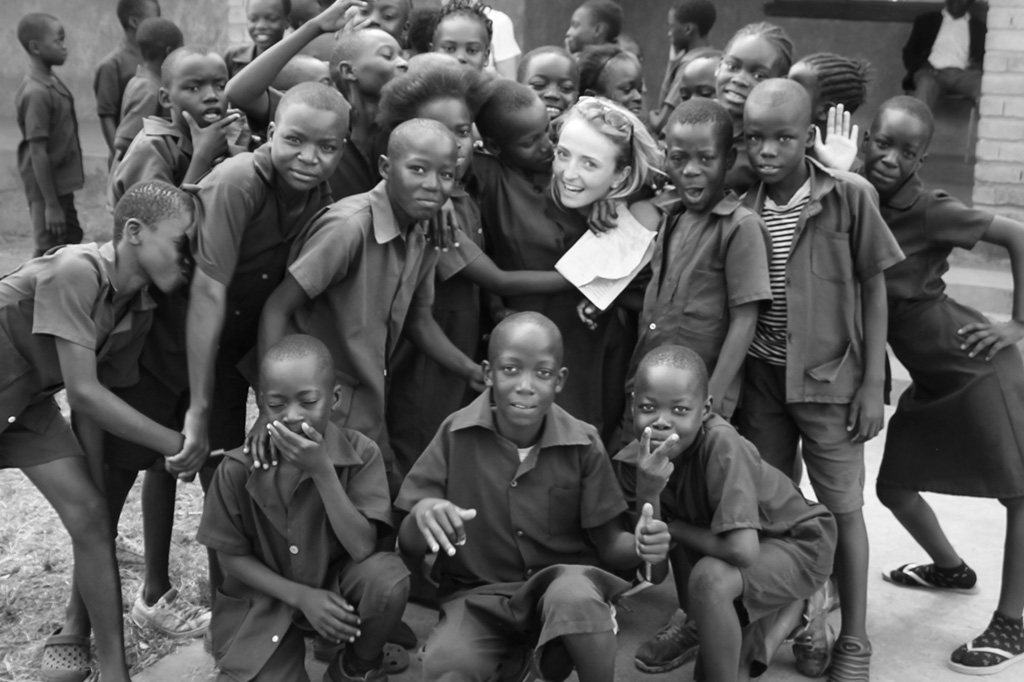

For my senior project, I traveled about 60 hours to a compound in Chipulukusu, Ndola, Zambia, and taught English at a day school for orphaned children.

I started my project with the intention of contributing to the essential component that they lack. The greatest limiting factor in African children’s English development is the exposure to the language, particularly in Zambia. It is vital for children to be exposed to English if they are expected to speak it as a second language. Throughout my time in Ndola, I came to realize that, in fact, English is not lacking as a whole. They do have a select number of teachers who speak it. Rather, they lack an exposure—exposure to a life different from what they are accustomed to seeing, exposure to an English that will offer them hope, and a life that is far beyond anything they’ve witnessed.

The Republic of Zambia is a geographically unique country in the southern part of Africa. It has a population of 14 million people. Ndola, the city where I was teaching, contains about 400,000 people. It is a city rich with diversity and various ethnic and racial groups; however, only 1.5 percent of the population speaks even a little English. There are many reasons why this landlocked country in sub-Saharan Africa has not failed economically, politically, or socially. Surprisingly, Zambia is considered one of Africa’s most stable countries. It does not face some of the brutal realities that are present in other parts of Africa. It is blessed with an abundance of natural resources such as gold, coal, copper, and many others. However, this is not to say that Zambia does not have its own significant challenges. “Not failing” is a very low bar to surpass.

Most of Zambia’s 14 million people live on less than $1 per day, leading to tragedy. In fact, one local man in Chipulukusu let me know that the average family, a family of about eight, lives on 60 cents per day. Over 65 percent of the total population of Zambia lives far below the poverty line. Food security, education, health, and poverty remain the most urgent and interconnected issues for the entire population. I believe that education is the primary connecting link. The rising threat of drought due to climate change-related natural disasters and changing global temperatures exacerbates all issues by diminishing the already poor food security and agriculture-based economy.

The Republic of Zambia remains in

the top eight countries globally with deaths due to HIV and AIDS. At dinner one night, I met a 23-year-old girl who takes care of

her five younger siblings on her own. But

this came as no surprise as this scenario stands for most families in Zambia. Nonetheless, I was shocked when we began talking about the epidemic, and she told me that she believes that seven out of every 10 women in Chipulukusu have HIV or AIDS. Luckily, she explained, there are exciting new clinics that have begun to pop up around the country in an attempt to slow the epidemic. The average age for pregnancy and marriage is between 12 and 16 for girls, so this effort becomes even more crucial. But again, Africans must speak English in order to obtain help from these HIV and AIDS clinics.

Today, the struggling poverty, health, and hunger levels continue to rise, making education a distant dream. But the irony, and the hope, is that the fundamental cure for these urgent crises is the very thing that is often inaccessible: education. And education, with the end goal of getting students into any workforce, bringing them further away from their current state of poverty, starts with speaking English. Today, it is the language of international communication and remains the most common second language in the world. Research shows that most cross-border communication is governed in English, and there is an explicit expectation that people must have English competency to communicate.

The importance of speaking English is clear. But, how did we get here to begin with? Orphaned children around the world are often a result of previously discussed issues such as unsatisfactory access to health care, education, and aspects of general well- being. These problems are generally considered a result of historical global exploitation compounded by social and political inequalities today. However, in the case of orphaned children in Ndola, Zambia has its own story. And, I am grateful to have experienced it in the way I did.

The New York Times published a story describing the “Abandoned Generation” in Zambia. It reads: “The AIDS epidemic has been raging in Zambia for nearly two decades, and as the deaths pile up, so do the orphaned children.” The United Nations says that Zambia has the highest proportion of orphaned children in the world, relative to population. In Zambia, 2 million children per year are being orphaned due to sexually transmitted diseases. While AIDS is considered preventable in many places, insufficient health services and education lead to high rates of AIDS and AIDS-related deaths in Zambia. Many people with HIV do not appear to be sick, so it is not apparent who has contracted the disease. Lastly, AIDS is an immune deficiency; the virus attacks the immune system, making those infected more susceptible to other diseases. So, many AIDS-related deaths are often attributed to other illnesses.

This death rate has resulted in millions of families, whom the children often call their stepfamilies, taking orphaned children into their own homes to keep them alive. Sadly, these native families in cities like Ndola do not have the funds to support or feed a child in addition to their own. As AIDS and HIV rapidly kill adults every day, more and more children are left homeless; thus, they are broke and have no access to basic life necessities like food and water, let alone healthcare and education. The cycle continues.

In 2005, a Zambian man named Emil Makuka partnered with a Sun Valley local, Peter Dubonne, to reach out to the vulnerable children of Ndola, Zambia. Together, Makuka and Dubonne found over 300 children living in a garage just big enough for two cars. These children had no financial support. They had no sustenance, no clothing, no school, no medicine, no clean water—no one who cared. They had absolutely no hope for their lives. So, the pair decided to dedicate their lives to creating a school in the compound of Chipulukusu, which, in Bemba the language of Zambia, directly means worthless.

Makuka was raised in Ndola and remains within the minority who graduated from university. Makuka and Dubonne cared; they intended to break the cycle. They created The Mapalo (meaning “Blessing,” rather than worthless, in Bemba) Morning Glow Academy. The academy supplies 400 students with a meal every day, has one freshwater well, and gives the orphans an education and hope for the future. The Morning Glow Academy follows the traditional African model of a non-residential orphanage and school. Without the academy, hundreds of children would still be starving, still fighting for education and well-being, and still facing a life without aim. Times are slowly changing.

The English that the children are learning will allow for opportunity that otherwise would not exist. It will allow for a continual education, a future in any workforce, an understanding of disease and poverty, and an expanded commitment to empower young people who deserve all that is out there. I have created a film that is meant to share my experience, but more importantly, share the students’. I hope that this film gives you the opportunity to understand and see the community for all that it is: both good and bad. And, most importantly, show the reason that your next “I have to” or “I need to” should start with an “I get to.”