Seeing the rich star fields and dust clouds of the Milky Way, appearing as a band of multi-colored, twinkling lights across the night sky, is a common experience in Central Idaho. But for the majority of Americans, the Milky Way is not visible. For most, light pollution obscures the night sky, making it impossible to see more than a few stars. The ability to gaze at a truly dark night sky is rapidly decreasing in America as urban centers expand and the most visible effect of light pollution—artificial skyglow—replaces our view of the cosmos.

A growing body of evidence linking the artificial brightening of the night sky with negative impacts on human health, wildlife, and ecosystems, as well as a growing concern over the loss of an important human experience—the opportunity to view and ponder the universe—is encouraging local leaders to take action toward protecting this resource. The communities surrounding the Sawtooth National Recreation Area are working toward putting Central Idaho on the map as America’s first Dark Sky Reserve. “People are beginning to recognize that light pollution is an issue, both nationally and globally, and that dark skies are a resource we need to protect,” said Dani Mazzotta of the Idaho Conservation League (ICL), who has been working on securing the Dark Sky Reserve designation from the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) with Central Idaho communities for almost two years.

IDA defines a Dark Sky Reserve as “public or private land possessing an exceptional or distinguished quality of starry nights and nocturnal environment that is specifically protected for its scientific, natural, educational, cultural, heritage and/or public enjoyment.” There are currently only 11 Dark Sky Reserves in the world, none of which are located in the United States. Reserves generally consist of a dark “core” zone surrounded by a populated periphery (or buffer zone). A key requirement is that communities within the designated Reserve commit to protecting the darkness of the core by minimizing their own light pollution. According to Mazzotta, a key piece in making the Reserve possible is that most of the proposed Reserve is already covered by local dark sky ordinances. “We don’t have to go in and create local ordinances and regulations because they already exist.”

Ketchum passed one of the first dark sky ordinances in the state of Idaho in 1999, with the intention of protecting the ability to view the night sky by reducing glare and unnecessary lighting at night. Other jurisdictions in Blaine County followed suit. The City of Ketchum was recently designated an International Dark Sky Community by the IDA.

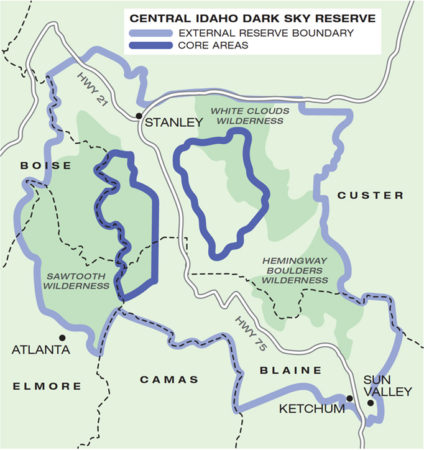

The Central Idaho Dark Sky Reserve would encompass over 900,000 acres, stretching from Stanley to Ketchum, including Sun Valley, Smiley Creek, parts of Blaine and Custer counties, and the SNRA, most of it public land owned by the U.S. Forest Service. This area is an ideal place for a reserve, as it has extremely few sources of artificial light. ICL has been using sky quality meters to take measurements of the sky and monitor light pollution levels in the area. The results are really good.

“The readings we are picking up in the Sawtooth Valley, between Ketchum and Stanley, are around 21.86 magnitude per square arcsecond,” said Mazzotta. During moonless nights, the luminance of a clear sky with light from only natural sources (the stars, the Milky Way, natural atmospheric emission) is about 22 mag/arcsec2. Attaining Reserve status will not only help protect this pristine night sky, but will also recognize the commitment local communities have made to support the night sky experience and encourage compliance with the existing ordinances.

“The readings we are picking up in the Sawtooth Valley, between Ketchum and Stanley, are around 21.86 magnitude per square arcsecond,” said Mazzotta. During moonless nights, the luminance of a clear sky with light from only natural sources (the stars, the Milky Way, natural atmospheric emission) is about 22 mag/arcsec2. Attaining Reserve status will not only help protect this pristine night sky, but will also recognize the commitment local communities have made to support the night sky experience and encourage compliance with the existing ordinances.

The Dark Sky Reserve designation also has the potential to attract a unique brand of tourism, astro-tourism. Interest in booking trips to see cosmic spectacles, like the Northern Lights, aurora borealis, solar eclipse and meteor showers is growing. The total solar eclipse this past August is reportedly the most viewed and photographed eclipse in history. In Eastern Idaho alone, it is thought to have brought in 300,000 tourists. Other communities have leveraged the night sky to promote visitations, events and activities. Jasper, Canada, holds a dark sky festival where they bring in high-level scientific speakers and have star watch events. The Utah Symphony played three evening concerts this year near National Parks and held “star parties” afterward hosted by local astronomers.

This interest in astro-tourism may be related to the decrease in ability to see starry skies. Currently, 83 percent of the world and 99 percent of U.S. and European populations live under light-polluted skies, while the Milky Way is hidden from view for more than one-third of humanity, including 60 percent of Europeans and nearly 80 percent of North Americans. As it becomes more difficult to view stars and planets, see the Milky Way, and catch occasional glimpses of galaxies and nebulae with the naked eye under light-polluted skies, protecting the remaining truly dark night skies is of urgent importance.