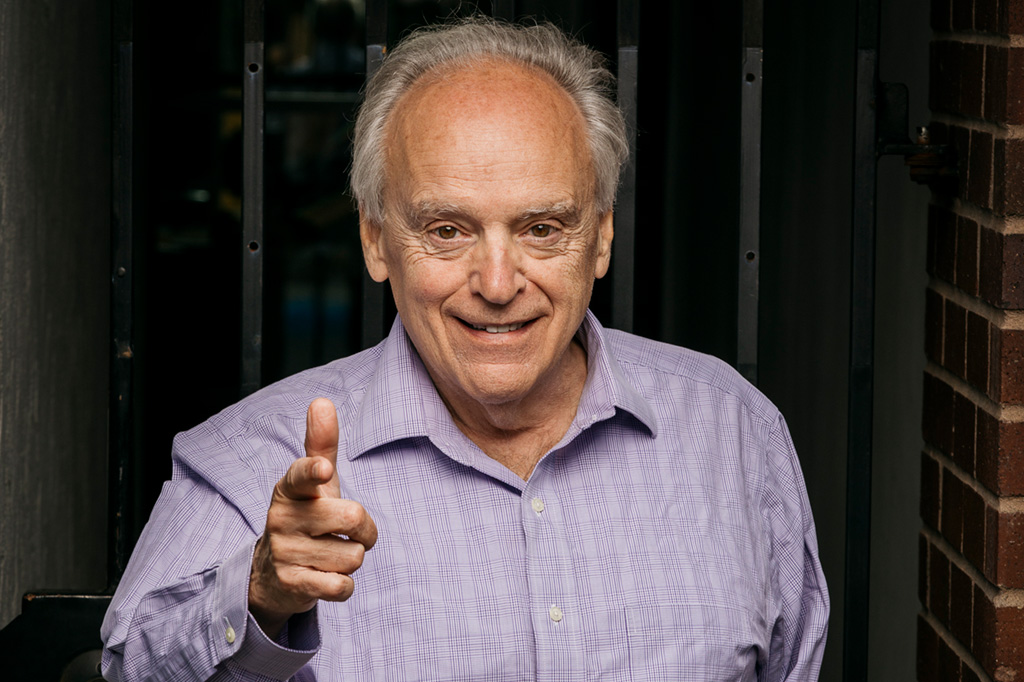

Charles Brandt is not what you would expect.

Brandt’s long legal career as a homicide investigator, prosecutor and chief deputy attorney general of Delaware would conjure an image of a steely, hardened man with little mirth. His tenure at the latter post in the 1970s witnessed some of the worst rates of violent crime in the nation, and Brandt personally investigated or prosecuted over 55 murder cases. But Brandt seems to carry little of those days with him now. Affable and warm, he is sincere, yet quick witted, keenly observant, and prone to spontaneous eruptions into song, usually singing small snippets of show tunes from the 1950s or his favorite Perry Como tune.

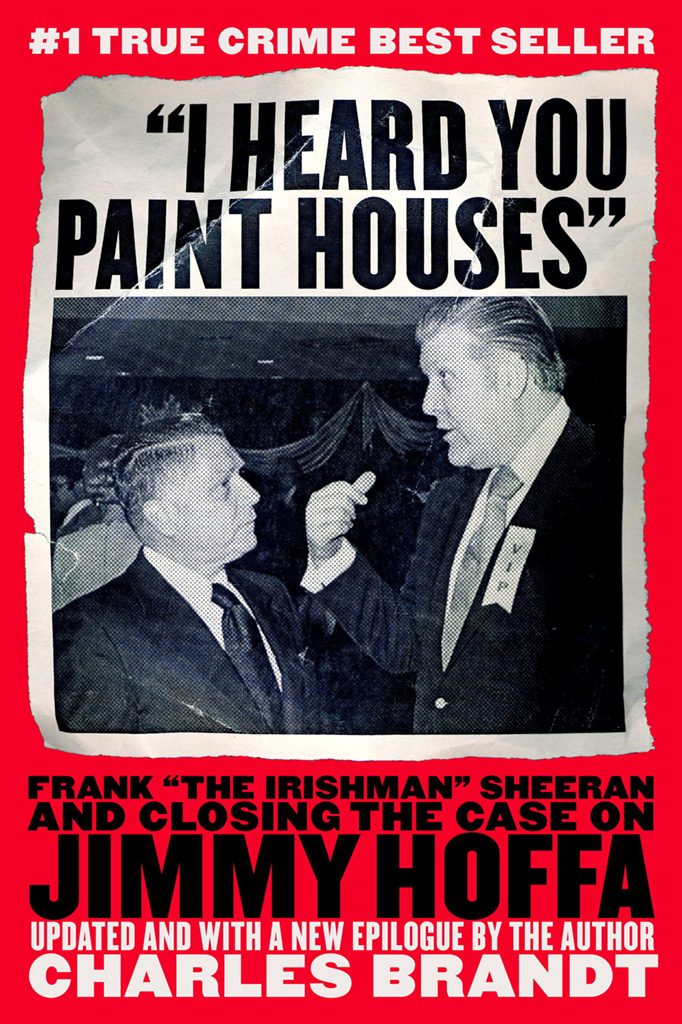

Recognized as an expert in interrogation and cross-examination, Brandt taught interrogation techniques to police officers and cross-examination to other trial lawyers but is perhaps most well-known for his 2004 release, “I Heard You Paint Houses,” a No. 1 New York Times bestseller that offers the biography and confession of Mafia hit man Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran. The book exposes the inside story of the Mafia and one of America’s most famous murder cases—the disappearance and murder of legendary Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa on July 30, 1975.

Hoffa’s body was never found, and his fate has been speculated about for decades in one of the world’s most famous missing persons cases. Theories exist about his body having been cremated, crushed by a 40-cubic-yard trash compactor, shredded in a chicken slaughterhouse, buried on a farm in Michigan, placed in a 50-gallon drum that was set on fire before being crushed and sold as scrap metal, and most famously, shot and dismembered, then frozen and buried in cement under the old Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J.

These are not exactly bedtime stories, and yet, Brandt sat with Frank Sheeran, Hoffa’s confessed killer and a Mafia hit man attributed with over 25 to 30 murders, almost daily for nearly five years gathering material for his book. The book was released in 2004 (with a second printing with 57 pages of additional material in 2016), the year after Sheeran died at age 83, and is now being made into a Netflix original movie directed by Martin Scorsese to be released this fall. The film stars Robert DeNiro, Al Pacino, and Joe Pesci; Academy Award-winning screenplay writer Steve Zaillian wrote the screenplay.

The movie was optioned back in 2009 and has been in the works for almost a decade, with the release pushed back at least twice to accommodate new material. Some of the new material was withheld by Brandt because he feared for his life and couldn’t release it while the principals were still alive.

Brandt—the grandson of Italian immigrants Rosa and Luigi DiMarco, who were illiterate, and the son of parents whose schooling stopped at the eighth grade due to family finances—began his career as a junior high English teacher in Queens and welfare investigator in East Harlem before applying to and graduating from Brooklyn Law School in 1969. His amiable and charming demeanor seems to mask a deep yearning for the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, and Brandt’s ability to “dig in” and keep the witness talking make him a worthy adversary to any hardened criminal.

But how did Brandt get Sheeran to confess to not only the Hoffa murder, but the murder of mobster “Crazy Joey” Gallo in the infamous gangland slaying at Umberto’s in 1972, Hoffa murder coconspirator Sally “Bugs” Briguglio, and several dozen others?

Sheeran was in prison for labor law violations, serving 32 years of jail sentences, when Brandt got a call from the Philly mob requesting his help in getting Sheeran out on an early medical release. Sheeran was about 70 at the time and Brandt and his partner pleaded his case before the parole board, securing his early release. After the celebratory lunch at Vicente’s, Sheeran pulled Brandt aside to tell him that he’d read “The Right to Remain Silent,” Brandt’s first novel based on his cases as a prosecutor in Delaware, and was interested in talking.

“He told me he was tired of being written about in all the books on Hoffa’s disappearance,” said Brandt, “and that he wanted to clear his name.” This was 1991, 16 years after Hoffa disappeared, and dozens of books and articles had been written about it with Sheeran mentioned in almost every single one as having a role. Nobody knew what role, because nobody was talking, but Sheeran was always a central figure. “He said he wanted to tell his side of it and he wanted me to write it,” Brandt said, “And instantly, in that moment, I knew he wanted to confess.”

“Frank gave me 80 percent of the material I needed in our first meeting,“ Brandt recalled. “I was trying to prolong the conversation because you don’t want your subject to ever step away and think about what they’re saying; you want them to just keep talking.” Sheeran had mentioned eight people involved in the ‘Hoffa thing’ and Brandt dug in, knowing the answer, but asking Sheeran why there were so many individuals involved as a tactic to keep him talking.

“That way, if you go bad, you only know what you did. You can’t rat on the other ones before you and the other ones after you,” Sheeran responded. “They’re definitely not going to have a massacre, but a lone cowboy will be disposable.”

Brandt dug in further, innocently making the correlation to Lee Harvey Oswald’s lone-wolf status in the Kennedy assassination, but remembers in chilling detail what came next. “Something changed suddenly in his demeanor,” said Brandt, who remembers Sheeran turning to stone and waving him off with his right hand, almost as if wiping him out of his vision. “I’m not going anywhere near Dallas,” Sheeran said.

Brandt said it was one of only two times he was ever truly afraid in Sheeran’s presence. Sheeran was just out of jail and his house was probably bugged, either by the Mafia or the FBI, or both. Maybe the mob thought Sheeran had been released from jail in exchange for telling secrets or had turned state’s evidence. Maybe they didn’t want Brandt knowing what Sheeran knew. Maybe they had both become a liability. Brandt wasn’t going anywhere near Dallas, either.

He wrote up the information related to the Hoffa brief and submitted it to Sheeran for review—Sheeran had provided new information but had not yet named the man who pulled the trigger. Sheeran turned to stone again and said, “You can’t use this material, these people are still alive.” So the two parted ways, with Brandt saying to contact him if he ever changed his mind. That was in 1991 and Brandt and Sheeren didn’t speak again for over eight years, when Sheeran called again.

As Brandt tells it in “I Heard You Paint Houses,” Sheeran’s daughter had arranged a private audience with a Catholic priest. Sheeran had grown up a devout Catholic, his father had studied for the priesthood and his mother went to Mass every morning, and Sheeran was seeking absolution for his sins so he could be buried in a Catholic cemetery. “After that meeting, Frank called saying he wanted to give the details to someone,” said Brandt, “and that someone was me.”

In over five years of taped interviews, Brandt began to unravel the details of Frank Sheeran, the man who confessed to killing his friend and mentor Jimmy Hoffa, as well as nearly two dozen others, in cold blood. Through hours and hours of almost daily conversation, Brandt teased out the details of what he calls Frank Sheeran’s unique and fascinating life, describing him as “the witty Irishman” who had a tough upbringing during the Great Depression

Sheeran enlisted in the Army, serving in the 45th Infantry, General Patton’s infamous “killer division” that was instructed to take no prisoners and paid heavily for their valor, suffering 21,899 battle casualties. Brandt estimates that Private Frank Sheeran served 411 combat days in World War II (when the average number was 80 days), surviving three amphibious invasions and liberating Dachau, and believes that it was during his “prolonged and unremitting combat duty that Frank Sheeran learned to kill in cold blood.”

But Sheeran didn’t enter into that life immediately. “Frank came back to America changed after the war,” Brandt said. He returned to America to reenter normal society. He got married, had several daughters, and was working as a truck driver when a chance encounter with mob boss Russell Bufalino changed his trajectory and the course of history forever.

“I was hauling meat for Food Fair in a refrigerator truck in the mid-fifties,” Sheeran stated in “I Heard You Paint Houses,” “when my engine started acting up in Endicott, New York. I pulled into a truck stop, and I had the hood up when this short old Italian guy walked up to my truck and said, ‘Can I give you a hand, kiddo?’”

The “short old Italian guy” turned out to be Russell “McGee” Bufalino, boss of the northeastern Pennsylvania crime family that bore his name and a man who had secret interests in Las Vegas casinos, connections to the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, and who was identified by the Pennsylvania Organized Crime Commission as a silent partner of the largest supplier of ammunition to the United States government. In a report of its findings, the McClellan Committee on Organized Crime of the United States Senate called Russell Bufalino “one of the most ruthless and powerful leaders of the Mafia in the United States.”

“Frank didn’t even know there was such a thing as organized crime until he fell in with the Mafia and became an integral part of it,” said Brandt, who became close to Sheeran over the years. “We were family, we did things together,” said Brandt, adding that “if the Mafia had ever suspected what Frank Sheeran was confessing to me, we would have both promptly been whacked.”

But it was a broken-down truck near the New York-Pennsylvania border around 1955 that brought the Mafia to Frank Sheeran, a 6-foot-4 Irishman and WWII combat veteran who was to alter the course of history 20 years later through his alleged involvement in the disappearance of teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa on July 30, 1975.

Bufalino and Sheeran became friends, having dinner together and becoming close (a fact that Sheeran said, unbeknownst to him, saved his life on at least two or three occasions). Sheeran handled certain matters for Bufalino when he asked, “never for money, but as a show of respect.” Maybe Bufalino represented the protective father figure that Sheeran never had growing up (Sheeran’s father would box him, using him as a punching bag, daily after school). Bufalino was the one who first introduced Sheeran to Hoffa. It was a job interview set up over the phone and the first words Jimmy Hoffa ever spoke to Frank Sheeran were, “I heard you paint houses.” According to Sheeran, the paint refers to the blood that gets on the wall or the floor when you shoot somebody. Sheeran told Hoffa, “Yeah, I do my own carpentry work, too,” which refers to making coffins and means you get rid of the bodies yourself.

At the end of the conversation, Hoffa asked Sheeran, “Do you want to be part of this history?”

“Yes, I do,” Sheeran replied, having no idea how much he really would.

• • • • •

Brandt said that until Sheeran drew his last breath, he wore on the same hand Russell’s gold-piece ring and the gold watch Hoffa had given him. He wore them both as a reminder of his loyalties. The jewelry symbolized the emotional and moral conflicts going on inside him, and Brandt believes the murder of Hoffa haunted Sheeran from the day he was ordered to do it until the day he died.

“When you’re as close as he was to two of the most powerful men of that era,” said Brandt, “you are going to be exposed to a great many things.”