When longtime Wood River Valley resident Alan Pesky was approached by a friend, who was also the president of MacMillan Publishing, to write a book, Pesky thought he’d share the wisdom he gleaned from his years in the advertising industry. Pesky’s publishing friend even introduced him to two possible co-writers, one an Emmy-winning TV writer. But Pesky did not feel inspired to write about business. Then Jenny Emery Davidson, the executive director of The Community Library, told Pesky she’d like him to meet a writer friend of hers. He never expected to meet his future co-author, Claudia Aulum. He teamed up with Aulum, who had never written a book before, and their collaborative effort was released this past September. More to Life than More: A Memoir of Misunderstanding, Loss, and Learning reveals the importance and value of relationships.

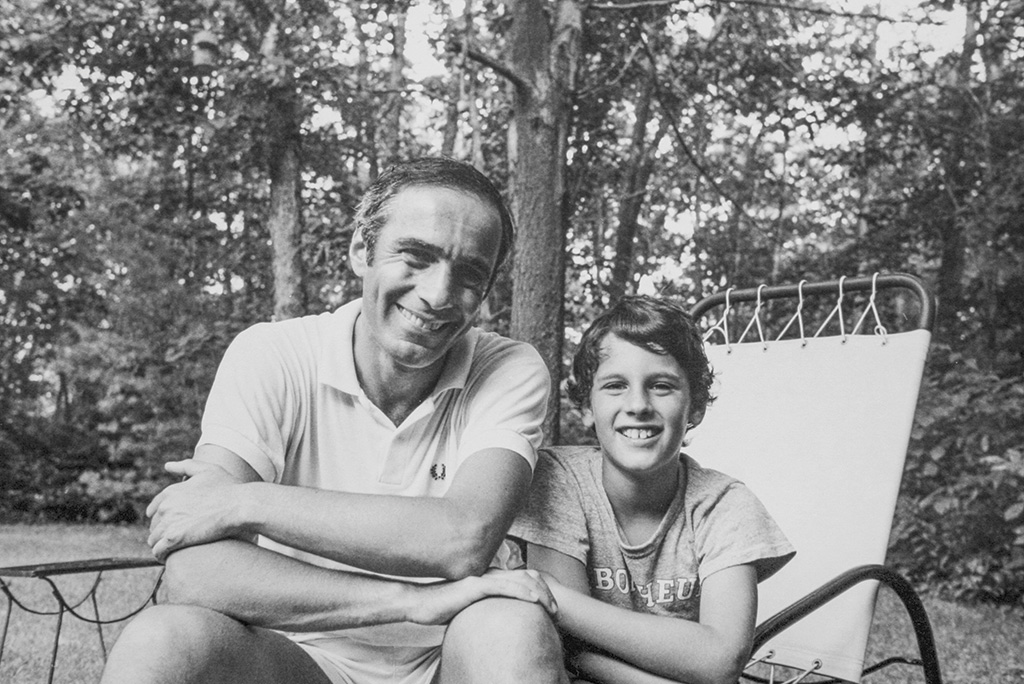

Emotionally riveting, Pesky’s book examines the layers of his often-difficult relationship with his eldest son, Lee, who had to overcome dysgraphia, a problem with organizing letters, numbers, and words on a page. A Kirkus Review described the candid and moving memoir as “an articulate, unflinchingly honest, and touching account brimming with joy, heartbreak, and love.” The memoir opens with the painful account of Lee’s illness and death. At the age of 30, Lee was diagnosed with brain cancer and passed away 10 weeks later on November 6, 1995.

To honor Lee’s legacy, Pesky and his wife, Wendy, established a facility for kids with learning disabilities in 1997. The Lee Pesky Learning Center, located in Boise, helps children with learning differences in ways that weren’t available to their son. “Our interest is to help kids fulfill their potential in life,” states Pesky, “to give them all of the tools they need under one roof.”

Pesky says that each child who comes to the Lee Pesky Learning Center has his or her own unique identity, or fingerprint. Remediation for each can be different. “Our job is to find the fingerprint and then adapt the tools to suit that child,” says Pesky.

“When you have a learning disability, it has nothing to do with your intelligence,” says Pesky. “It’s the way your brain is wired. If it’s not wired exactly right, it manifests as a learning disability. You cannot cure a learning disability, but what you can do is explain it to the person who is diagnosed with it.” This eases some of the frustration. “The problem with the child who has a learning disability isn’t the child. It’s everybody around the child who doesn’t understand. Don’t blame the child. Understand the child.”

“Lee grew up when ‘learning disability’ was not in the English language,” says Pesky. With few resources available at the time, Lee’s family struggled to find the support Lee needed to overcome his obstacles to learning. Lee graduated from Lafayette College and became a business owner. “One of my favorite memories of Lee,” says Pesky, “was watching him at the Buckin’ Bagel—loving what he was doing, how happy he was—he was experiencing success.” Lee, the founder of the Buckin’ Bagel chain, had opened two branches in Boise and was planning to expand when he became ill. Another favorite memory is Lee bending over to kiss his pregnant sister’s belly and saying, “Hi baby, this is your Uncle Lee.” In the last picture of Lee, he is wearing his Buckin’ Bagel hat, holding his sister’s baby.

When asked what message he wants readers to take away from his memoir, Pesky says, “Love the child you have, not the child you want.” He notes that sometimes parents have expectations of their child—they want the child to have an interest or talent in an area that interests the parent. Pesky wanted Lee to be athletic like him, but Lee had motor control problems. “If you want the child to be something and that child doesn’t fulfill that dream, that’s something you should understand—you should not be upset by how that plays out. Have the freedom to understand the child you have.”

Pesky continues, “Love comes in different forms. It manifests itself differently. I have enormous love for all three of my children (Heidi, Lee, and Greg). I wish Lee was here today so I could put my arms around him and say, ‘God, I love you. You’re pretty terrific.’”

At a BSU commencement, Pesky addressed Idaho teachers and said, “Although I have always had an interest in education, it wasn’t until we opened the doors of the Lee Pesky Learning Center that it became the focal point of my life. It has given me a totally different perspective of the important role education plays in the life of an individual and on the broader scale for our society.”

“The biggest thrill I can get in life is to see a kid who wants to come to the Learning Center because we’re making progress,” says Pesky. He noted that the Learning Center has impacted not just the lives of the children it serves, but also the families of which they are a part. To have a parent tell him that he’s changed their lives or saved their child’s life, “that is what ‘more’ means to me.”