There was a time when Ketchum’s charm relied heavily on its history; it’s one of the reasons why the Ketchum and Sun Valley areas have remained near and dear to those who have been visiting for 40-plus years; it’s not like a typical mountain town. The vibe and the Tyrolean architecture helped lay the groundwork for the culture.

However, instead of log cabins, brick houses and the rustics that make mountain towns captivating, a giant crane is the first thing you see when you enter Ketchum. That crane is being used to build a new four-story hotel across the street from the relatively new Limelight Hotel.

Our little town has been growing and growing fast. Lately, it seems to be under permanent construction between the roadwork and the workforce housing projects, which are all necessary additions and improvements. But sometimes, with all the new, we need the reassurance and balance of the old.

Thankfully, we’ve still got that with some of our favorite old haunts and bars and a triad of genuine historic buildings that aren’t going anywhere any time soon.

Why do we care about historic buildings? It’s human nature to wonder and care about where we come from. Stories are great, but buildings form a tangible representation of another time.

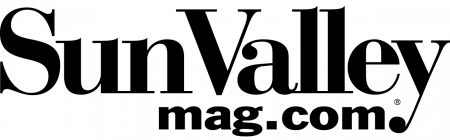

Ketchum proudly showcases three unique and historic brick buildings. Isaac Ives Lewis, a banker from Butte City, Montana, was among the first to set foot in what is now Ketchum.

In the spring of 1884, Lewis joined George Griffin to build the First National Bank of Idaho on South Main Street. This building has been home to Chapter One Bookstore since 1970 and now Rocky Mountain Hardware, which faces Main Street.

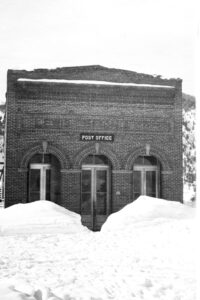

That same year, Lewis built the Lewis & Lemon Co. general store across the street. This eventually became Griffith Grocery, The Golden Rule store, Iconoclast Books, the Cornerstone Bar and Grill, and now Sun Valley Culinary Institute.

The Lewis & Lemon Co. general store and post office circa 1925.

Finally, the third point to Lewis’ brick triangle: in 1887, he built the Comstock & Clark dry goods store, which eventually became Lane Mercantile, a supply headquarters for the booming sheep ranching industry. Enoteca restaurant can be found there now, but the back of the building still proudly tells passersby to EAT MORE LAMB.

There’s just something about brick. It’s simple. It’s basic. It’s irreplaceable. A real brick house (not a frame built with a brick façade) can withstand even the most violent storms. A brick building is mostly impervious to fire, pests, and rot. Bricks can reduce sound and even offer a certain level of insulation. We know how labor intensive the laying of bricks is, so we know that someone cared—someone built that building to last longer than their actual lifetime.

Preservation societies understand that we can continue strengthening our community’s image and identity by caring for our historic buildings and sites. These goals can be threatened by the reality of personal property rights as well as development pressures. Still, once a building is demolished, all we have left are photographs or newspaper clippings.

With all the new construction, having the landmarks and touchstones that feed our basic human need for continuity and meaning is reassuring. When things start to feel overwhelming and alarmingly unpredictable, putting your hands on something solid feels good. We need to know that some things are permanent. Modern times have brought great complexity, and maybe we yearn for simpler lives, the way things were in the “good old days.” ï