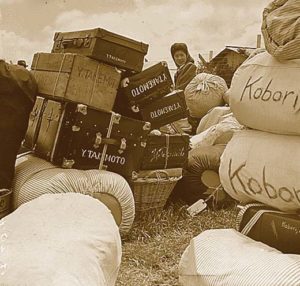

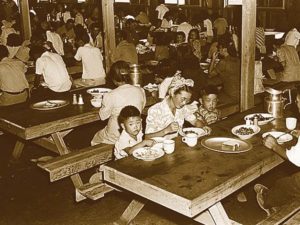

Internees unload at the Minidoka detention camp near Twin Falls. At its peak, the camp held 9,397 people of Japanese ancestry and was the eighth largest city in Idaho.

The bus rocked across rutted dips as it worked its way through the sprawling, fertile farmland on the outskirts of Twin Falls, Idaho. The rich, irrigated greenery of this place stands in sharp contrast to the barren scrub desert Takeshi Yoshihara remembers from 67 years ago, when he and his family were taken from their Portland, Oregon, home by the U.S. government, put on a train, and brought here, the middle of nowhere.

“The land has turned so green. It is so different,” he said quietly as he gazed through the bus windows. “It looks beautiful, not what it was back then. It doesn’t yet bring back memories.”

Yoshihara, 78, and his 21-year-old grandson, Andrew, have joined more than 100 others from around the country on this annual pilgrimage to the former Minidoka World War II Japanese Internment Camp. Six decades ago, armed guards and barbed wire kept nearly 10,000 Japanese-Americans imprisoned here. Yoshihara lived in Minidoka with his parents and eight siblings for four years as a teen. From this internment, he grew up to become the first Japanese-American to graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy, and a captain during the Vietnam War.

The pilgrimage is hosted each year by the Friends of Minidoka, an Idaho-based organization that supports education and research focusing on the Japanese-American internment experience and works to uphold the legacy of those who were incarcerated.

Yoshihara is joined on this day by 34 fellow former camp internees. Still more are friends and family. Some have come simply as a call to social justice and to learn more about what happened here more than six decades ago.

“At the Mercy of the Country”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, authorizing the forced removal and incarceration of more than 115,000 people of Japanese descent who lived in the Western United States. Two-thirds of them were Nisei, the American-born citizens of Japanese immigrants, known as Issei.

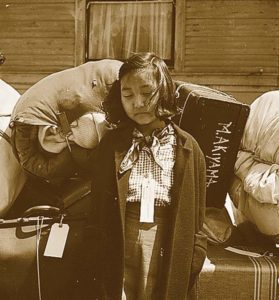

The evacuation happened quickly. Families took only what they could wear and carry. Most of what they left behind was sold, vandalized or stolen, and when they were released years later, they re-entered a society still seething with anger over the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor.

As Yoshihara said, “When my family left the camp, we literally had nowhere to go. We were at the mercy of the country.”

For Aya Uenishi Medrud, 84, the chaos began immediately after Pearl Harbor. FBI agents arrived at her home in Seattle in the middle of the night, handcuffed her father, accused him of being a “dangerous enemy alien,” and took him to a Department of Justice detention camp for suspected “troublemakers.” She was 16 years old.

She describes how the agents ransacked the entire house, including her bedroom, where they dumped her dresser drawers on the floor. As her father was led away, he told her it had become her responsibility to take care of the family. “I was just a girl,” she said.

In the days that followed, Medrud’s father’s assets were frozen. Without a second income to fall back on, her family was adrift. “We lost our property and our house. We had no money at all. We didn’t know where they took him,” she said. “I could not understand why this was happening to him. He was an accountant and a Buddhist and very non-violent. But I learned since then that it was probably because he also taught martial arts, and that was enough to consider him dangerous at the time.”

Within months of the arrest, Medrud, her mother and two siblings were sent to a Civilian Assembly Center at the Puyallup County Fairgrounds in Washington State. They lived in a dirt-floored horse stall for four months there. Such Civilian Assembly Centers served as temporary holding sites for the thousands of evacuated Japanese-Americans while the more permanent internment camps were being constructed.

A total of ten camps were eventually scattered throughout California, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah and Arkansas. Minidoka, sometimes called the Hunt Camp, was located at Hunt, Idaho, an unincorporated rural area named after Frank W. Hunt, a former governor of Idaho. It officially opened in August 1942, and its population peaked at 9,397, making the camp Idaho’s eighth largest city at the time.

A young woman amidst piles of luggage in 1942, just prior to transfer to a War Relocation Authority Center. |

Two children of the Mochida family who, with their parents, await the evacuation bus in Hayward. |

The Administration Building at the Minidoka Relocation Center in Hunt, Idaho, an unincorporated rural area northeast of Twin Falls. |

Once at Minidoka, Medrud began writing letters, at least a dozen, she said, to President Roosevelt, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and others in authority telling them the United States had no right to keep her father in prison and to release him. “I eventually received a response that essentially said, ‘We’re sorry we had to put your father in prison but there is no way he can be released.’”

In February 1943, all internees aged 17 and older were required to complete a questionnaire designed to separate the loyal Japanese-Americans from the disloyal. Called an “Application for Leave Clearance,” two of the questions asked about their willingness to serve in the U.S. military and whether they’d be willing to deny allegiance to Japan. “Yes” answers to both would indicate their loyalty to the United States. Medrud’s father answered correctly and was reunited with his family in Minidoka in December 1943. The camp closed just under two years later in October 1945.

Today, most of the 33,000 acres that once comprised Minidoka are privately owned farms, with about 73 acres set aside as the Minidoka National Historic Site, managed by the U.S. Park Service. The camp’s original 600 buildings, gardens, playgrounds and swimming holes are long gone, but this hallowed ground still awakens buried memories and strong emotions from revisiting pilgrims.

Coming Back

The bus rolled to a stop in front of an old camp warehouse. Yoshihara smiled and said, “Happy memories are coming back, a connection is here. I don’t really regret being here, except that it was not right. But otherwise, there are good memories.”

We were met by our guide, Mike Wissenbach, a Park Service employee who walked us through the remains of the area. As the camp visitors stepped off the bus, two Buddhist priests in yellow robes beat on Japanese hand drums and chanted a blessing. Wissenbach lead the group through the buildings that remain—a storage warehouse, a firehouse, a root cellar and two of the original barracks that are now kept at the nearby Idaho Farm and Ranch Museum.

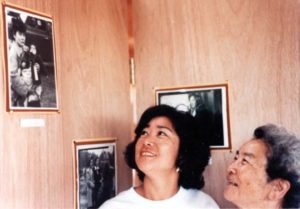

Here, the bonds created so long ago again became apparent. Masako “Massie” Endo Hinatsu stooped to share a map of the former camp site with two other Japanese-American women and discovered that the three of them had been childhood friends in Minidoka more than six decades ago.

Hinatsu, 78, had just turned 12 when she arrived at Minidoka with her mother and five brothers and sisters. Stepping inside one of the preserved barracks, she reflected on life inside the cramped box.

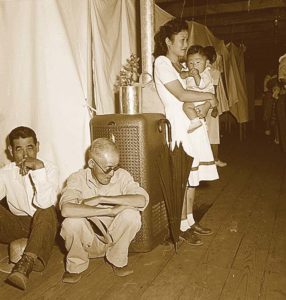

“There were seven cots that we had to line up somehow in the room,” she said. “I can remember in the wintertime it was really cold, and we would stuff the pot-bellied stove full of coal, and it would get red-hot. We had no place to hang our laundry, and we would hang strings all across the room. And we had a bare light bulb,” she said, pointing to the one stark light fixture hanging from the middle of the plywood ceiling.

The poorly built barracks were not much more than wooden frames covered in tarpaper. There was no insulation to ward off the brutal winter cold or the stifling summer heat. Inside, they had no running water, no kitchen or toilet facilities, and blinding dust storms blew dirt and grime through cracks in the walls. Hinatsu recalled that when it rained, the mud outside the barracks became ankle-deep, sucking boots right off their feet.

“I remember my mom putting us on her back to take us over to the mess hall, because it was so muddy,” Hinatsu said with a laugh.

When internees first arrived, a sewer system had not been built, forcing residents to brave the bitter Idaho cold and stench of a primitive outhouse. Eventually, toilet facilities were communal, a difficult adjustment for many.

“What I remember of the wash house is it had no partitions between the toilets,” Yoshihara said, adding that it was an uncomfortable setting for him as a shy boy. “There were about 20 commodes, all in a row out in the open, and everyone used it together. The women had the same situation. It is hard to imagine today.”

Four internees outside a barrack in 1944 at the Minidoka internment camp in southern Idaho. Photograph courtesy Densho and the Okawa Family Collection.

Making the Best of it

Despite harsh conditions, internees found ways to rebuild their lives on the Snake River Plain. They collected scraps of lumber and sagebrush to build furniture and shelves and ordered cloth for curtains from mail-order catalogs, which they bought with the small allowance they received each month. They built small parks, a baseball diamond, and flower and produce gardens.

Many living in the camp went to work in camp offices, canteens, mess halls, hospitals, schools and the fields, earning wages ranging from $8 to $16 per month.

Those who were children during the war often say they remember many happy times at Minidoka. Yoshihara recalled learning to swim in the Snake River. “I would jump in, and the current would take me around to the bend,” he said. Others talked about walking to the camp school with friends, playing sports and even going to movies that were occasionally shown in camp. Medrud remembers ice skating on the nearby pond.

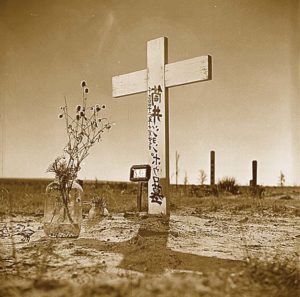

Not all “evacuees” returned to their homes-many found permanent relocation in grave sites like this one in eastern Colorado, pictured in 1945. |

|

A young evacuee guarding the family baggage in 1942. |

|

A family inside a typical barrack apartment unit where cloth partitions were hung for privacy. |

The Twin Falls Community:

Acceptance and Rejection

From the camp, the bus took the pilgrims to the Twin Falls Red Lion Hotel for “Talk Stories,” a time set aside for internees, family and friends to share their memories of what it was like to live in Minidoka during the war.

Over the years, as internees died, their stories of imprisonment disappeared with them. Many Issei and Nisei chose not to talk about their experiences, leaving the younger generations of Japanese-Americans uninformed about events that rocked their forbearers’ lives.

“I can only explain it as refusal to accept what really happened,” Medrud said. “There are two Japanese expressions. One is gaman, which essentially means ‘to tough it out.’ The second is shikata ga nai, which roughly means ‘cannot be helped, it is out of my control, therefore accept.’ One conclusion I have come to is that this thing that happened to us, this incarceration, is so demeaning that we will not acknowledge that it happened. It is a form of denial.”

During Talk Stories, Medrud recalled the day a Minidoka administrator gathered the internees around a flagpole and announced, “You people killed my son!”

“I was 18 at the time and was stunned to think someone who ran this camp would have no sensitivity about who we were,” said Medrud.

“Two-thirds of us were American-born citizens, and my parents had lived here for many, many years.”

The greatest irony in this story is that, despite their internment, many young men in Minidoka also volunteered for military service. About 1,000 internees went to fight for the U.S. while their families remained at camp. As one Talk Stories speaker said, “Imagine, your parents are being held in their country of choice, behind barbed wire, behind armed guards, and you are volunteering to go fight for the government that put them there.”

Several local residents, all Caucasian, who had either lived near the camp during the war or were otherwise connected, also shared memories during Talk Stories. They talked of unlikely friendships, of how the internees helped area farmers with their crops, how internees transformed the land and how their incarceration had affected them as neighbors and friends.

As one speaker noted, internment didn’t just happen to the Japanese-Americans, it happened to America.

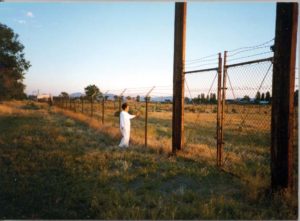

A former internee next to a barbed-wire fence at a former campsite.

|

This Japanese-American women took a photo of themselves during the 1942 mass-removal of persons of Japanese ancestry from their homes. |

The Rev. Brooks Andrews of Seattle’s Japanese Baptist Church was a boy when his father, Rev. Emery Andrews, regularly ministered to Americans of Japanese descent. “My father founded the Japanese Baptist Church in Seattle, and after Pearl Harbor and Order 9066 came out, the church was empty,” he said. “Dad stood in the pulpit and looked out at the pews and remembered the faith of the people who were missing. I was only 5 years old when he told me we were going to Twin Falls, Idaho, because that’s where our people were now.”

As supporters of Japanese-Americans, the Andrews family was given an inhospitable reception in Twin Falls. “My father was refused service and picked up and thrown out of the cafe by the owner,” he said to the crowd gathered for Talk Stories. “That same man would stand on the sidewalk in front of our house and call us traitors and turncoats and Jap-lovers. Finally, the man bought the house we were renting, and he forced us to move.”

He paused. “So we moved across the street to another house,” he said to laughter and applause.

Jerry Kleinkopf, a football coach at Twin Falls High School whose father was superintendent of education at the Minidoka Camp, recalled the day a neighbor said to his father, “‘You’re teaching them Japs? You ought to be shooting them instead of teaching them.’”

Kleinkopf emphasized how area farmers in the 1940s would have had a nearly impossible task of harvesting their crops without the help of the internees. “At the time, you couldn’t just go out and buy new farm equipment,” he said. “The people who made tractors were making tanks. Minidoka residents were eager to work and provide labor for the farmers,” he said.

Twin Falls resident Judy Gibson held up a pair of intricately beaded, fringed and lined leather gloves and explained that the internees in Minidoka had made them for her father who worked at the camp. “My father had polio that affected his hands, and they came to him and asked to make a tracing of his hands so they could make these gloves for him, to fit him exactly,” she explained. “My father really cared about them, and the people cared for him, too.”

The Good Side

The incarceration of Japanese-American people has been described as one of the worst violations of Constitutional rights in American history. The majority of the prisoners were U.S. citizens by birth.

Even so, some who were imprisoned see another side to it.

“I have no hard feelings,” said 88-year-old George Tsugawa, who was sent to Minidoka at age 21. “My parents came to America from Japan for a better life, for freedom of religion and opportunities. I think this experience made us better people. We had to try harder. There’s still not another country like the U.S.A. It’s the greatest country in the world.”

Dr. Ruby Inouye Shu, retired physician and Minidoka internee, agreed: “I have no bitterness, because I also look at the good side. If it weren’t for the internment and the war, the Japanese people may have just stayed concentrated on the Pacific Coast and not gone eastward. But we assimilated with other people and taught them that we were okay. So, I have to look at the benefits of internment. I mean, the whole thing is wrong, but if you look at the good side, it’s that now Japanese people are all over the United States.”

“But,” she laughed, “that’s just the good side.”

– George Tsugawa

She said that the closing of camps brought with it their own set of problems. “My father was more worried about leaving the internment camp, because while they were in camp they were given housing and food and they could work and there was nothing to worry about,” she said. “But when they were taken out of the camp and on their own, what would they do to take care of a family? A lot of people had nowhere to go. They had lost everything. That was more of a worry than going to a camp.”

Mealtime at the Manzanar, California Relocation Authority Center, 1942.

Karaoke, Prayers and Wishes

Following a barbeque hosted by the nearby Prescott Ranch, many in the group gathered at the Red Lion Hotel for cocktails and karaoke. Some former internees joined in to sing the old cowboy song, “Don’t Fence Me In.”

In the morning, we returned to Minidoka for a closing ceremony. The American flag was saluted, and former internee Kay Endo read the honor roll—names of internees who served in World War II. Then, as was typical during the entirety of this emotional weekend, tears were shed as Rev. Brooks Andrews offered a prayer.

“Lord, we come today having traveled a road that has stretched back some 67 years…But we are not overwhelmed. We are over-comers.

As we tell our stories and listen to other stories, we realize that each one of us is a hero of our own story. Thus, we redeem the history of this event…And so we grieve not, but take strength in what remains. Amen.”

A small piece of paper resembling the Japanese daruma doll was given to each person. The daruma is a symbol of wishes for the future, and the custom is to color one of the doll’s eyes while making a wish, and then the other if the wish comes true. We each make a wish and pin the small paper darumas to an 8-foot-tall replica of a guard tower.

It’s hard not to guess that many of us made the same wish—for what happened here 67 years ago to never happen again.