Destiny would have had Sigi Engl following in his father’s trade as a stonemason building tombstones for the Catholic Church in the tiny medieval town of Kitzbuhel, Austria. But fate, in particular an encounter with Adolph Hitler, had other designs. And so, the 5-foot-11 blonde Austrian went on to turn the Sun Valley Ski School into the finest in the world.

“No question it was the top ski school in the world under Sigi and Sepp Froehlich,” said Ketchum resident Ralph Harris, who grew up with Engl’s children and went on to become a ski instructor under Engl. “Sigi and Sepp were total icons, building the biggest and best ski school in the world. People came to Sun Valley from all over the world to learn to ski because of Sun Valley’s reputation. And, of course, Dollar Mountain provided absolutely splendid learning terrain.”

It was Harris who designed the bronze statue of Engl and Froehlich that stands in Sun Valley Village. Modeled after a photograph of the two men walking side by side, it was instigated by the ski instructors who revered the two men who had run Sun Valley’s ski school for nearly a quarter century.

Siegfried Engl went to the University of Innsbruck to hone his artistic skills. And he did create one tombstone, according to his daughter Nina Carroll. But he also excelled in ski racing, even taking ballet classes to finetune his skills.

He won the Italian downhill and slalom championships at Cortina in 1931, the slalom championships at Garmisch-Partenkirchen in 1932, the famed Hahnenkamm combined and the Marmolata downhill in 1935 and the Austrian slalom and downhill championships twice, earning a spot on the Austrian FIS World Championship team.

Sepp teaching class

At age 15, he learned to teach the Arlberg method of parallel skiing under Hannes Schneider, the father of modern skiing. And he found himself teaching the Prince of Wales and other celebrities, including impatient Americans whom Schneider noted wanted to “go-go-go” and learn faster than Europeans.

After winning the German combined national championship slalom and downhill, Engl went up to accept his medal. When he refused to return Hitler’s “Heil Hitler” salute, knowing that doing so would turn him into a propaganda piece, he was essentially blacklisted, said his son Michael Engl.

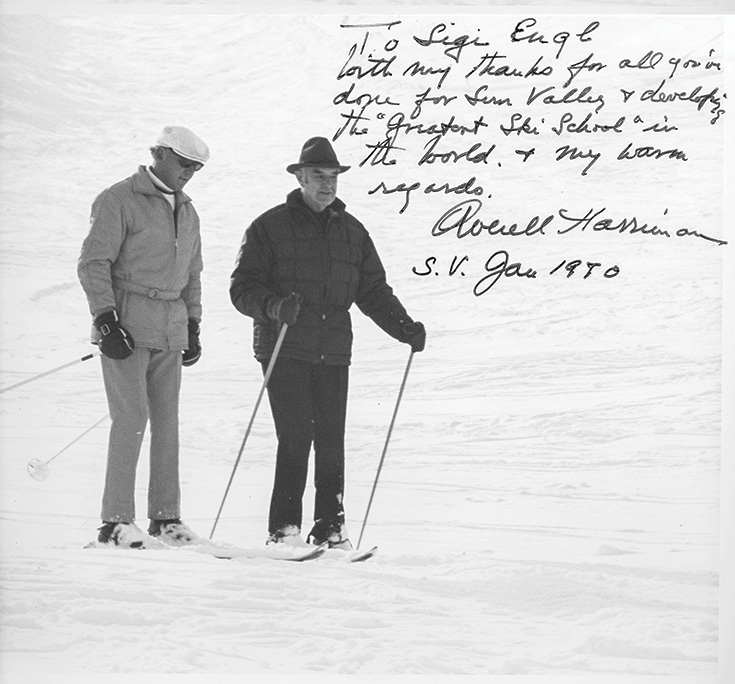

Sigi with Averell Harriman, who later signed the photo

“He couldn’t ski, couldn’t teach. And when the church fell into the hands of the Nazis, my grandfather was forced out of his job by Nazis who instructed him to move certain graves outside the church graveyard to make room for high-class citizens who paid good money to be buried there,” said Michael.

Donald Tresidder, the fourth president of Stanford University, learned of Engl’s predicament and invited him to America to help start a new ski school at Badger Pass Ski Area in Yosemite National Park. Tresidder had led the construction of the ski area, the Ahwahnee Hotel and park roads.

Sigi in a publicity shot with Cary Grant

Engl arrived at Ellis Island in 1936. He didn’t have a middle name as required, so authorities opened the Bible and assigned him the name his finger fell on: Joseph. He crossed the country by train, playing Christmas carols for passengers on his small Austrian accordion. “He was very musical, a good singer and a good yodeler,” said Carroll.

After spending a year working at Badger and scouting the Eastern Sierra for a site to build his own ski resort, Engl jumped on the chance to come to Sun Valley in 1939 to teach skiing.

Sigi with Groucho Marx

He made a name for himself in Sun Valley, winning the 1941 Harriman Cup downhill, tying his trousers with string to cut down on air drag. He became one of a rare group to win the Diamond Sun award for a harrowing race that started at the top of Baldy and went down Ridge, Rock Garden and Exhibition. And he met a girl, Peggy Emery, a co-ed at Sarah Lawrence College, who had come to Sun Valley to ski.

“My father had a date with actress Norma Shearer, who wasn’t a skier but liked the Hollywood culture of Sun Valley. And my mother was dating a Basque ski instructor,” said Michael Engl. “They had dinner together in the Duchin Room, switched dates, and not long after that, Norma took the ski instructor back to Hollywood, straightened his teeth and they went on to have a fabulous time.”

As the United States entered World War II, authorities took some of Sun Valley’s German and Austrian ski instructors to Twin Falls and Salt Lake City to interrogate them about their allegiance.

“I was treated well. I have no complaints. I was released and then I volunteered for the Army,” said Froehlich, who was in custody for 16 months, charged with being an enemy alien. “I knew, if I wanted to stay in the country, I should do the job.”

Count Felix Schaffgotsch, who had recommended that Averell Harriman build a ski resort in Sun Valley, elected to return to Germany and fight with the Nazis. Froehlich didn’t want to fight against his countrymen, so he opted to fight in the Pacific, where he was awarded a Bronze Star for gallantry.

Engl avoided incarceration by enlisting right away. But before he went, he married Peggy. They held their reception in the Duchin Room at the Sun Valley Lodge, honeymooned all of one night in a Shoshone hotel, then Engl headed to Colorado where Sun Valley’s ski instructors comprised the core of the Tenth Mountain Division.

From there, Engl headed to Sicily where he accompanied American troops the length of Italy, serving under General Mark Clark as an interpreter for German prisoners of war. He and his Austrian comrades were also able to guide American troops through the mountainous area of northern Italy because they’d hiked and skied in those very mountains.

When the war was over, Engl and Froehlich were among the many Austrians and Germans who returned to Sun Valley, where they earned more money than they could at home. Engl even had a chance to ski Sun Valley before it reopened when he was summoned to escort Gary and Rocky Cooper, Clark Gable, and Ingrid Bergman around Ruud Mountain, which Gary Cooper had rented so they could use the chairlift.

Engl was promoted to head of Sun Valley’s ski school in 1952. And Austrian ski jumping champion Froelich joined him, the two always kidding each other in a good-natured rivalry because they’d come from different parts of Austria. Together, they expanded the ski school from 50 instructors to 200 with three of the biggest names in international skiing: Stein Eriksen, Christian Pravda, and Jack Reddish.

“When I got to New York City in my late 20s, I was astounded at how the Irish and Jews and other nationalities were always looking down on others because the Germans, Austrians, Swedes, Canadians, and Americans at Sun Valley had all worked together after a horrendous conflict,” recounted Michael Engl. “My father told his instructors, ‘If I hear anybody talking about the war, you’re going to be sent back home. This is a new start. This is not reminiscing. Let’s hold ourselves in the present.’”

Skiing on extraordinarily long skis in leather boots, Engl made long sweeping turns across the snow, always wearing the white driver’s cap pioneered by Hannes Schneider to distinguish him from his instructors.

“He was very good at hiring good instructors. He’d go to Kitzbuhel every year to interview candidates. He liked Austrian teachers because they all taught the same way,” said Carroll. “And he was very good at matching students to instructors.”

He was also a firm disciplinarian, a man so focused his family had to beg him to stop for gas on the drive to see relatives in Pasadena.

He required instructors to meet for 4:30 p.m. ski school meetings seven days a week at the Sun Valley Opera House. He would give the weather forecast. And he sometimes turned purple, shouting in a staccato voice, if some instructors had done something to earn his wrath that day, said Bert Cross, who decided that teaching skiing was easier than swinging a pick for $1.50 a day to build the highway over Galena Pass.

“He was very Germanic. He talked with military precision. And he was very organized—you couldn’t get away with anything,” Harris said. “Sigi would get on stage and put on a tough guy performance with his Austrian accent, making sure everyone knew he was in command, and there was no messing around.”

Those who crossed the line were tasked with raising the ski school flag in the morning.

“He was strict, but he had both the love and respect of the 200 people underneath him,” said Carroll. “He was severe on them when they did wrong, but he offered total protection if anyone attacked him.”

“He was an authority, and he needed to be,” said Jed Gray, a lifelong resident of Sun Valley. “These were mostly young men, and Sigi laid down the law and stuck with it.”

Engl and Froehlich met every skier as they got off the big yellow buses at the turnaround in the village ahead of a week of ski lessons. They’d assign them to a group of ski instructors. And by 9 a.m., there would be a thousand skiers lined up Baldy and Dollar Mountains, taking turns skiing so instructors could determine which group they belonged in.

Engl was in high demand among such celebrities as Jackie Kennedy, Claudette Colbert, Betty Hutton, Groucho Marx, Clark Gable and Janet Leigh, who didn’t want to ski with anybody but the ski school director.

“Follow me,” he’d say as he danced through the snow on a non-stop run of swinging turns known as christies. “Look always forward,” added Froehlich.

“I think skiing with these people made him feel important, but he didn’t brag about it,” said Carroll. “Even though the celebrities were always around, we weren’t overly impressed with them because we didn’t know to be impressed. Dad didn’t come home and tell us, ‘Guess who I skied with today…’”

One of his toughest challenges was the Shah of Iran who had come with 16 bodyguards, none of whom could ski. Four ski patrollers were given guns and enlisted to accompany him. Engl insisted on skiing ahead of the Shah, but the Shah did not want to be taught. He just wanted to ski and ski fast. And occasionally, he would zoom by Engl.

“I will be a hero in my country if I’m hurt skiing,” the Shah told Engl, when Engl cautioned he was skiing beyond his ability. “I will be a bum in mine if you’re hurt,” Engl replied.

On another occasion, Michael Engl said, the Shah wanted to ski down Canyon from The Roundhouse following a party of caviar and champagne. Engl arranged for ski patrol members to hold lighted torches for him on one side of the run, but the Shah skied down the other side in his wide snowplow. When the Shah insisted on doing it again, the ski patrol followed with a toboggan. But they only needed it to fetch a ski patrolman out of a snowbank.

Mammoth Mountain skier Travis Reed asked Engl to teach him after he realized he needed instruction if he were to keep up with his wife. “I looked all over, and everyone said there was only one place to learn to ski, so I got an outfit made in Beverly Hills, blue with racing stripes. Sigi looked at me up and down, an astonished look on his face. He said, ‘Can you stem on steep hill?’ And I said, ‘I hope not.’ And he went, ‘Ohhhhhh,’” Reed said, mimicking Engl’s frustrated look at realizing his would-be student knew nothing.

As the 1950s evolved, skiing became less of a sport for celebrities and more of a sport for families, and Engl was quick to embrace the change.

“You don’t see any children in the movie ‘Sun Valley Serenade.’ But when Lucille Ball came to shoot her show here, it was proof that family skiing was in the spotlight, that that would be the future of the sport,” Michael Engl said. Engl started a program on Saturdays for school kids in Blaine County to get free ski lessons.

“I always went on Saturdays when the classes were not full because, after six days of class, people wanted to ski on their own, or they were exhausted or partied out. Sigi always put me with the best instructors,” said longtime Sun Valley resident Peter Gray.

Engl was one of the first to use video, mounting a camera in a tower where the Quarter Dollar lift sits now. Skiers would then watch themselves on a large TV at the bottom of the mountain where they could slow the action and stop it as they analyzed their moves. The Community Library has a video of Engl teaching people to ski, making pizza shapes with his skis, then drawing the skis closer together, making a little hop as he prepares to turn.

He also instituted races on Dollar Mountain on Thursdays and races on Warm Springs on Fridays, with the top three people in each class winning pins at parties in the Limelight Room.

“He promoted a camaraderie between instructors and students so that, by Wednesday, everyone was exchanging business cards, and by Friday, students were inviting us to their homes in New York City and elsewhere,” Harris recalled.

That said, Engl could be a little protective of his turf when it came to ski racing, said Dick Dorworth. “Sigi was of the mind that European skiers were much better than Americans. In 1963, when he learned that Ron Funk, Tammy Dix, Betty Bell, and I were planning on skiing the Diamond Sun, he tried to put a stop to it. Fortunately, Walter Hofstetter was mountain manager at the time and overrode Sigi’s edict. Ron, Tammy, and I all qualified and got our Diamond Suns, and I have to admit that my pleasure and sense of accomplishment was enhanced by Sigi’s chagrin and unhappiness with us.”

In the 1950s, Sun Valley Resort was surrounded by a sea of sagebrush. Engl’s family was allocated room and board in the Sun Valley Lodge and later the Challenger Inn as part of his contract. The children ordered off a children’s menu or selected items from the cafeteria buffet.

“I remember being served by a waiter in a dark suit and white gloves. We ate adult food—I don’t remember having a hot dog, ever,” said Carroll. “We attended preschool for Sun Valley employees’ children at Trail Creek Cabin. And when the hotels closed for painting and maintenance during slack, we’d play hide and seek, jumping up and saying ‘Boo!’ when someone showed up.”

Engl was a popular guest at parties organized by Sun Valley Resort. He would ski all day, lead his 4:30 p.m. meeting, then attend cocktail parties and dinner from 6 to 9 p.m. before dancing in the Duchin Room. Sometimes, he would attend parties at the home of Win and Anita Gray, who were only too happy to pitch in and entertain Sun Valley guests.

“All the celebrities wanted to meet locals, and Sun Valley arranged that,” said Jed Gray. “The resort would provide the food and staff, and Mom and Dad would invite locals to attend.”

Engl and his wife loved Broadway musicals and were always playing such albums as “The King and I” at home. “My dad also liked to dance,” said Carroll. “My mother had Parkinson’s, so she could not be very active, but she enrolled me in dance lessons with a teacher from Boise to learn the foxtrot and ballroom dancing. Once I learned those steps, my father would take me dancing.”

“He loved doing the jitterbug with me and an Austrian dance called the Kiss Waltz, where you form a window with your arms, then the man tries to kiss you through that window,” continued Carroll. “He had a firm grip when he danced, his hand in the middle of your back. He knew how to lead. And he loved hugs—always bear hugs.”

All the instructors were encouraged to mingle with guests, said Cross in an oral history given to the Regional History Department. “I was kissing my girl by The Roundhouse, and Sigi said, ‘You’re not supposed to neck with the employees. Save that for the guests!’ He was a good director. He tried to be father/confessor. He thought of himself as a father figure.”

Froehlich, who spoke with a much more pronounced accent than Engl, worked as a hunting and fishing guide during summer. He used to take Anita Gray and her sons, Jed and Peter, trolling for trout on Sun Valley Lake and pheasant hunting along Silver Creek.

“He was a no-nonsense guy,” said Peter Gray. “I was 8 or 9 and a pheasant got up in my feet, and I was startled, and he laughed at me and said, ‘That’s exactly how it’s supposed to go.’”

Engl worked as a tennis pro for Pete Lane’s and accompanied Lane on shopping trips for ski goods.

“I was a tennis ball gatherer, but I made my money hunting golf balls in the rivers and selling them to guests,” said Michael Engl. “I made so much money, my mother was certain I would never learn the value of money.”

When Bill Janss bought Sun Valley Resort, he and Engl clashed over their vision for the ski school. Janss, whose bid to ski in the Olympics was thwarted by World War II, wanted to turn Warm Springs into a racing mecca, and Engl wanted to continue to focus on traditional instruction.

Promoted to Director of Skiing in 1972, Engl continued to keep an eye on his ski instructors but from a distance. Eventually, he retired but he always continued to ski with those people who’d been coming for years, such as the editor of the Chicago Times.

“He took up golf after belittling it for many years and became totally addicted to it,” said Michael Engl. “He got down to a three handicap.”

Engl died in 1982 at 71 years of age. Froehlich died the same year at age 73. By then, Engl had been elected to the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame and awarded Austria’s Golden Medal of Honor for distinguished service. Sun Valley renamed No Name Bowl to Sigi’s Bowl in his honor.

“He loved Sun Valley,” said Carroll. “And he made it a better place.”