Quebec artist Paul Béliveau is removing the romanticism of pop culture and burning the edges of classical written works. He’s ripping the content from its context and pairing it akin to a new anatomy. Smoldered novels. Warped spines. Burned pages. All on a larger than life canvas of supine geometrical books.

He says it might have something to do with the 60s. Hippies.

“The hippy generation left an impression on me,” Béliveau explained in a recent interview. “It’s a type of personal nostalgia.”

While attending Laval University in Quebec City for a Bachelor of Arts degree in Visual Arts in the 60s, he was recognized for his brilliance in drawing, engraving, and painting. Today, his accomplishments include over 100 solo exhibitions across Canada, the United States, and Europe. Béliveau’s paintings are hyper-accurate representations of famous books and iconic celebrities. Two particular collections will be displayed at Gilman Contemporary in Ketchum June 24 – July 26.

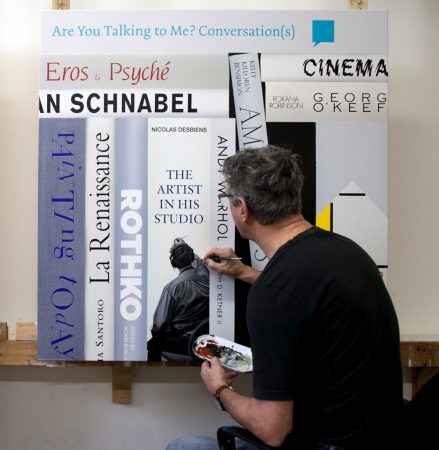

One series is titled “Vanitas.” It’s a collection of paintings comprising fictitious book spines displaying titles that, however subtly, connect to one another. Iconic artists across a spectrum of genres and subject matter intersect: Michael Jackson, “Picasso’s War,” Wayne Thiebaud, Jack Kerouac, Anthony Burgess, John Steinbeck—artists hailing from different disciplines with their life’s greatest works precariously posed on the spines. It is as if their own artistic developments were pages and pages of a spellbinding novel. For that is the impact it left on Béliveau.

“The ‘60s were the years of my adolescence,” Béliveau said. “They were marked by significant cultural changes in music, visual arts, politics, religion, science and aerospace.”

A great amount of information about the world is absorbed during the adolescent years. Béliveau is attentive when letting these influential experiences artistically seep into his paintings and drawings.

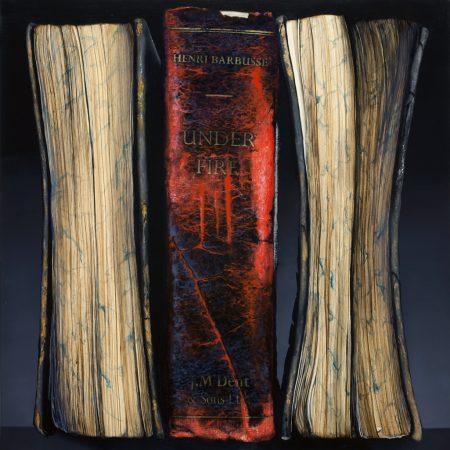

The second series to be exhibited is “Autodafés.” It is a complement to “Vanitas” with its exposition of classical works and their writers: Albert Einstein, Ernest Hemingway, Sigmund Freud. These are artists who were controversial in their respective time periods. And they’re all burned. The pages curl up at the edges in charcoal crisps, though the titles are just legible.

“The ‘Autodafés’ series is not unlike that of the Nazis who burned more than 20,000 books on German universities,” Béliveau said. “It proves that our culture remains fragile and at the same time burning a book is also a Promethean gesture: By fire we obtain knowledge.”

Béliveau’s work travels between genres and initiates a contemplative conversation of idealized elements. They build upon each another as the construct of a society builds upon itself with varying opinions, values, and laws. It’s a wink from the artist to the world relaying their most captivating thoughts.

Over the years, Béliveau has created a rich body of work appreciated by many who have followed his development as an artist. And the way in which he chooses to work reveals that it is a lifestyle for Béliveau, from sun up to sun down. His day begins promptly at 7 a.m. Of course, that’s after a 15-kilometer bike ride from his home on the south side of Quebec City and a ferry ride across the St. Lawrence River to reach his multi-workshop studio. There he sips an espresso with the brilliance of Bach concertos playing in the background before beginning work.

He has two assistants who help him three days a week and a full-time partner, his spouse, Manon, who has worked with him for 20 years. She handles the accounting, communicates with galleries and museums, manages local and international shipments, and keeps inventory of his work. She also helps with the lettering on the paintings and puts the final varnish on his works.

His home hosts a third studio with 12-foot ceilings and is well lit by natural light pouring in through large windows. At home, he continues his research and documentation for new paintings.

“I devote around 10 hours a day to art and creation,” Béliveau explained.

The term “utopian library” is the construct of transformation and an intimation of thematic convergence that Béliveau will be exhibiting at the Gilman Contemporary show.

“I often use the term ‘utopian library’ because, in general, the book spines that the viewer sees do not exist as is,” Béliveau said. “It allows me to be more creative and thus to design a work where image, color, and typography allow a more dynamic reality.”

Gilman Contemporary owner L’Anne Gilman was introduced to Béliveau’s work by a client who had commissioned a piece. She says that she fell in love with his work and was immediately interested in seeing his new paintings as they were created.

“I admire Paul not only for his talent as a photorealist painter, but for his unique ability to tell a story in how he places these imagined books together,” Gilman said.

With his artwork rendering a new mixture of time-warped ideas, Béliveau says that he hopes to create an encounter between the writer, the historian, and the reader.

“The fact that ‘Vanitas,’ ‘Autodafés,’ and also ‘In Memoriam’ series interact with each other, it gives weight to these reflections that, hopefully, will give the viewer the taste of reading, which is the door to knowledge in the digital age,” Béliveau said.