If there’s a limit to Wood River Valley giving, it seems to be the sky. For the sporadic volunteer or the well-heeled benefactor, there may be no more immersive place to wade into philanthropy. The journey can begin with a conversation with one of hundreds of nonprofit employees on the slopes, or on the lawn at the Sun Valley Summer Symphony, where a symphony staffer might share a personal affinity for The Hunger Coalition.

Days in the lives of Blaine County residents and visitors often include contact with the nonprofit world. Coffee with someone from The Advocates battling domestic violence, or breakfast with a NAMI volunteer building awareness about mental illness, could lead to a walk with a dog at the Animal Shelter of the Wood River Valley. Perhaps it’s the weekend of one of the most famous annual fundraisers, the Sun Valley Center for the Arts Wine Auction, arguably the winningest annual fundraiser in the county, possibly even in the state.

Using a computer at The Community Library, Ketchum’s oldest nonprofit that got its start with a cadre of beneficent women in 1955, a person could choose to help fund a Wood River Women’s Foundation grant. Those who drop tips for workers at the Sun Valley or Galena lodges enable the generosity of those in the service industry. Others may dream about winning next winter’s Janss Pro-Am Classic that just celebrated its 20th year in support of ski education. Winding down with a little Charlie Rose on Idaho Public Television in one of the Valley’s hotels, it’s hard to miss that Mr. Rose’s interview show is underwritten by Allen & Company, an organization long entwined with the Valley.

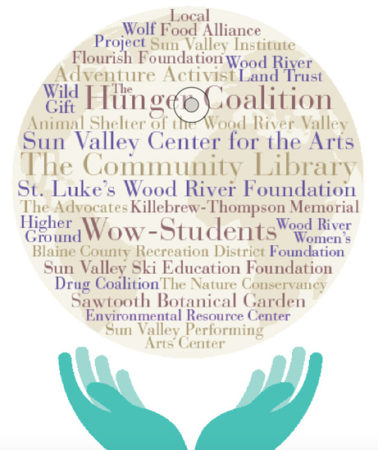

There are so many charitable organizations to help put one’s money where one’s mouth is in the Sun Valley area that the culture of giving stimulates benevolence well beyond county lines. Arguably, the nonprofit sector has become the heart of the community (as well as an economic engine; 72 nonprofits in the Valley reported $72 million in revenue for 2013/2014). The tipping point may have been when Kiril Sokolov helped bring His Holiness the Dalai Lama for a community-building workshop in memory of 9/11 in 2005.

Callan Miranda, Special Events Fundraising Manager and Wine Auction Director for the Sun Valley Center for the Arts. Photo by Kirsten Shultz

Although the Sun Valley Center anticipates the Wine Auction to cover about half its annual budget, in 2016, the blowout—which includes wine lots, of course, private rock star parties, other one-of-a-kind experiences, and super vacations, among many auction prizes—raised a record $1.9 million, and it’s been pulling in over a million dollars for years. A chunk of the auction money goes to throwing the weekend party that ends with a community picnic that thousands look forward to attending, but, nationwide, the event is one of the most successful of its kind and allows The Center to offer most of its programming free.

Callan Miranda, special events fundraising manager and Wine Auction director for The Center, points out that giving is a personal experience. “We give to causes which are close to our hearts, and which we believe better the world around us,” she explained. “Each year, attendees of the Wine Auction choose to support arts education, as they believe in the difference The Center makes in creating compassionate, curious and contributing members of our community. We are grateful that so many share The Center’s ethos and value the work we do enough to contribute to our organization.”

Morley Golden (in back), founder of The Wood River Foundation’s Wow-Students, a philanthropy training ground for some 4,000 students in the County. Photo by Kirsten Shultz

There are many ways to give of one’s time, talent and treasure, says Morley Golden, founder of the Wood River Foundation’s Wow-Students, a philanthropy training ground. Some 4,000 students in the county place their bets (seeded by donors) on programs in the community that help young people not only see the tangible results of giving, but also to experience the process of giving. Of the dozens of Blaine County nonprofits, many are connected to a greater ecosystem that includes statewide organizations like the Idaho Conservation League and even international groups like The Nature Conservancy that have been active in the area for decades.

Now, after decades of patiently reading the philanthropy tea leaves, the nexStage Theatre is about to gain a world-class tuneup, as it is likely to break $10 million in its own capital campaign for a new structure on the nonprofit’s property.

The theater group joins the ranks of entities like the Animal Shelter, Community School, the Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation, and the St. Luke’s Wood River Foundation that over the last 25 years has expanded hospital services well beyond the barebones of Sun Valley’s historic Moritz Community Hospital. Today, an E.R. staffed with board-certified physicians, state-of-the-art robotic navigation system for spine surgeries, and an expansive new infusion suite for patients undergoing chemotherapy are available—services unheard of at a 25-bed rural hospital. Such capabilities not only enable patients to avoid traveling out of the Valley for complex care, they also bear on decisions by businesses, conference groups, and families in deciding whether to come to the Valley in the first place.

The Sun Valley Road Rally is a summer fundraiser for the Blaine County Drug Coalition, a nonprofit that helps families avoid the scourge of drug addiction. The work happens in the background of an annual police-sanctioned speed spectacle. As speeds and proceeds top 230 mph and $400,000, respectively, it’s a modern-day almsgiving that also triggers adrenaline. It’s a clear philanthropic motive coupled with hedonistic pursuit—in other words, a classic fundraiser win-win.

Certainly, fast cars are not an inexpensive hobby and the sacrifice can’t hold a “commitment to cause” candle to running an ultra-marathon to fight cancer, or a solo standup paddleboard epic across the Atlantic to raise millions for The Lunchbox Fund, Operation Smile, and Signature of Hope. But who’s to judge? One person’s death march is another’s adventure.

Mouse-click crowdfunding has helped to democratize giving, allowing millions to shout down the 1 percent descended from robber baron philanthropists whose names are on the country’s oldest libraries dating back to days when this place was part of the huge Alturas County of the historic Idaho Territory. Blaine of today has it all.

How and Why We Give

For some, the goal is to save polar bears and even the New Jersey shore from climate change. Others give to help the Sun Valley Ski Patrol or the White Helmets of Syria Civil Defense secure new defibrillators. For still others, those with the wherewithal to buy naming rights on the new wing of a hospital, or, in the nexStage example, naming the performing arts center is important. Self-interest runs the gamut when it comes to philanthropy. Of course, there are beneficial tax implications for giving. The tax code, in all its complexity, invigorates at least high-level giving and helps to fund the nonprofit world, which, by some calculations, drives 12 percent of the Blaine County economy, well beyond the state and national averages for the sector. And that’s without the huge nonprofits that aren’t necessarily charitable organizations, like Battelle Energy Alliance, that runs facilities such asxs the Idaho National Laboratory under the U.S. Department of the Interior. Battelle, like many large organizations, nonprofit and for-profit, do maintain foundations for giving alongside their main enterprises like The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which contributes widely in Idaho.

While the peripheral motivations for giving are myriad, at its core, the effort is an altruistic one, and one that, ironically, can be transformational for the donors.

Buddy Wilton has long been a champion of philanthropy, having served on numerous nonprofit boards, including that of St. Luke’s Wood River Foundation, the U.S. Ski Team and the Baptist Health South Florida Foundation. The Association of Philanthropy recognized his generosity, naming him Virginia’s philanthropist of the year in 2003. For Wilton, philanthropy is “being part of the community you live in. It is an opportunity to help others and make where you live a much better place. Giving is as easy as breathing. We must all do it. The greatest job of all is giving to others.”

Donations, grants and fees for services keep local nonprofits rolling along, but fundraising events happen almost weekly in the Valley, not including the big events like the annual Idaho Gives day organized by the Idaho Nonprofit Center each May.

Megan Thomas, Chief Development Officer, St. Luke’s Wood River Foundation. Photo by Kirsten Shultz

An increasingly common and effective way to make a mark for good is in estate giving. Many Wood River Valley residents have worked with estate planning professionals to leave parts of their estates to benefit favorite nonprofits. Megan Thomas, chief development officer of the St. Luke’s Wood River Foundation has developed a “legacy-giving” program for the hospital, one that she is working to export to other nonprofits in the Valley. “Generous estate gifts have made a transformational difference for our hospital,” Thomas said. “Planned gifts, such as bequests or charitable trusts, can be an advantageous way to provide for a future gift. You can take care of yourself and leave a lasting legacy in the Wood River community.”

Even with a legacy gift—some are able to give a few dollars and others can fund a few salaries—it is worth exploring the dynamics of giving today. How disparity impacts society is on display even in a relatively affluent place like Blaine County. Some say the disparity is stark. To that end, nonprofit professionals have made Blaine County home, in part, because giving is dynamic and reliable and the causes connect in a positive feedback loop, one that frequently fills in for the State of Idaho’s meager social services sector.

Carter Hedberg, Director of Philanthropy, The Community Library. Photo by Kirsten Shultz

Carter Hedberg, the former executive director at the Sawtooth Botanical Garden and development chief at Western Watersheds Project, is the new director of philanthropy at The Community Library, which is about to embark on a new capital campaign. He’s a transplant from the private sector in Minnesota.

“We are doing some exciting things,” said Hedberg, who, in his free time, has also volunteered with the Animal Shelter and the vestry of St. Thomas Episcopal Church. “The thing that comes to mind, speaking of generosity, is how this community has filled gaps when other social services haven’t. The State of Idaho runs pretty bare bones. The Community Library receives no government tax dollars. Hospice care here is privately funded. The Crisis Hotline is also privately funded through philanthropy. Imagine if we didn’t have the library or great hospice and a crisis hotline. It is a very generous community.”

A quick glance at The Hunger Coalition’s remarkable impact report shows that the organization has a deep community reach, simply considering the donor list, which includes even anonymous donations as high as $200,000. It’s clearly a beloved organization in the community and its ever-expanding programs, including the Bloom food truck with its book library curated in cooperation with The Community Library, is a novel offshoot with great potential as a service with the reach of the ubiquitous ice cream truck. In combination with other fundraising community-wide, a large donation came in recently from the sale of a historic Flying Squirrel chairlift chair. Half the proceeds went to The Hunger Coalition and half to the Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation.

Jeanne Liston, Executive Director of The Hunger Coalition. Photo by Kirsten Shultz

“We have donors in our community that support multiple causes,” said Jeanne Liston, The Hunger Coalition’s executive director, who recently gave a TEDx talk on the subject of addressing a persistent need for food that grew out of the Great Recession. It is a ‘round-the-clock effort that has gained wide support in the community and changes the lives of recipients and donors alike. “I think we have an organization that is easy to partner with. When I think of philanthropy, I think of gratitude. People are grateful for the blessings in their lives and we create a culture of gratitude at The Hunger Coalition.”

“People give because it feels good,” said Brooke Bonner, a founding board member of The Hunger Coalition and a key visionary for the evolving Animal Shelter of the Wood River Valley that is about to break ground on a $12 million project to build a new Animal Welfare Campus. “The vast majority of our donors are those that a charitable deduction on their taxes makes very little financial difference to them. In fact, more than half of the Animal Shelter’s 1,400 donors in 2016 gave less than $100. These grassroots supporters are critical to our success, just as our large donors are. When people give, whether $5 or $5,000, what is important is that the gift is significant to them and that they share the vision of the recipient organization. Giving to something you care about makes you feel a part of something bigger. You are helping build a better world. That’s not an esoteric ethical principle. It is a visceral feeling of belonging and self-worth.”

Brooke Bonner, Director of Development at the Animal Shelter of the Wood River Valley. Photo by Kirsten Shultz

Bonner has been actively working in the nonprofit sector for more than 15 years, but her interest began long before as an Idaho kid with a love of animals and the environment.

“I have these ridiculous pictures from my childhood where I’m practically covered in animals, and I seriously credit the cat … for helping me grow into a functional, compassionate adult. I had her for 22 years, starting at age 5. She moved with me from Idaho to California, to Maryland, and back to Idaho, and it about killed me to leave her behind when I went to college in New Jersey. But she was still there when I graduated, and didn’t seem to hold a grudge for our time apart. In my current work fundraising for the Animal Shelter, when I tell people we are not just helping animals, but also truly changing people’s lives and making better humans, I can say it with the conviction of my own experience.”

While giving one’s time, talent or money would seem a simple and isolated transactional event, that couldn’t be further from the truth. The multitude of ways local philanthropic projects reach into the world is incalculable and marvelously unpredictable. Be it a contribution to the Somali community in Boise, or to a wolf researcher Ph.D., it is hard to know the ultimate course of giving. Take, for instance, Peter Haswell. He’s from an island devoid of predators (Great Britain). He once bunked with wildland firefighters of the U.S. Forest Service in Ketchum and volunteered with the Defenders of Wildlife on the Wood River Wolf Project’s non-lethal methods for protecting wolves and sheep. Today, his research has taken him to Croatia, and he’s the co-author of a Journal of Mammalogy paper: “Adaptive use of nonlethal strategies for minimizing wolf–sheep conflict in Idaho.